Inside a conference room in a building overlooking the Janet Harvey Hall on Glasgow’s River Clyde, Sir Simon Lister laid out a clear ambition for British warship production: pace, precision, and purpose.

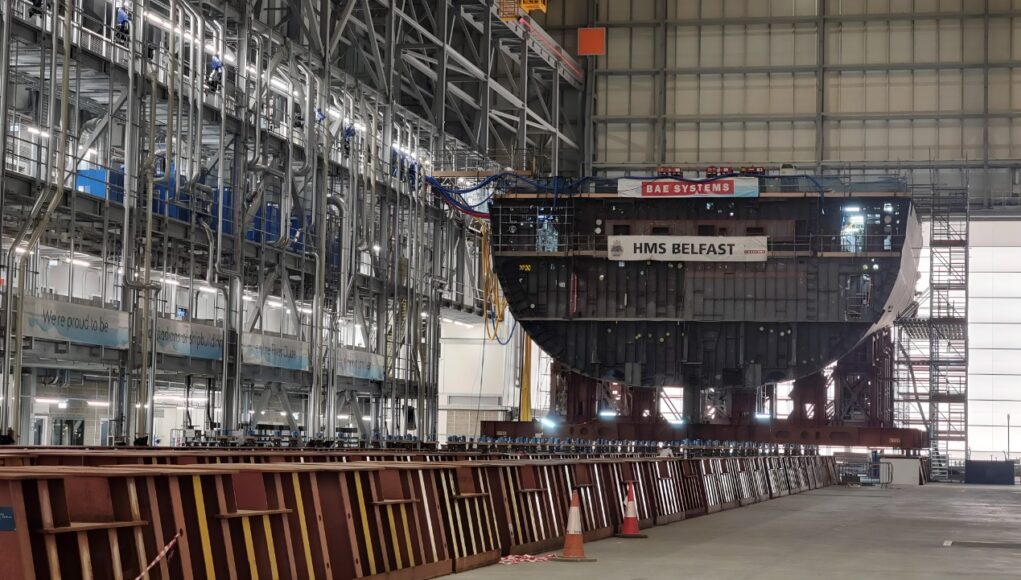

The new shipbuilding facility, one of the largest covered yards in Europe, is central to a transformation that aims to deliver Royal Navy frigates faster than ever before—and potentially bring export orders back to the Clyde for the first time in decades.

Lister, Managing Director of BAE Systems Naval Ships, described a future where warships are not just built, but engineered as “nodes in a network of military capability.” Speaking at a media briefing, he explained, “The word I never really understood when I was the customer of this organisation was ‘integrating.’ Integrating complex things—like the programme, like the technology—that’s what BAE Systems does. We take the customer’s requirements, which are really quite sophisticated in terms of lethality and stealth, and we translate those requirements into metal, into nuts and bolts, into a computer system.”

He emphasised that while many associate warship construction with steel, the true complexity lies elsewhere. “People tend to focus on the steelwork. Actually, that’s a small part of what we do. It’s the spectacular part, but that ship really takes a supercomputer to sea.”

Cutting build time by a third

Inside the new hall, shipbuilders are working to compress the build time of the Type 26 frigates significantly. “We’re aiming to build the fourth Type 26 in 66 months,” said Lister. “From ship one to ship four we aim to improve the performance of the yard by 30 percent.”

That’s a substantial leap forward from the first-in-class, HMS Glasgow. “We’re moving from building a prototype—HMS Glasgow—and the prototype is always a giant. No surprise there. But we’re now moving into series production of a ship that we are confident we can produce one every year,” he said.

According to Lister, weatherproofing alone has transformed the productivity. “We’re taking a third out of the time to build the ship. The quality and efficiency with which we build will be so much greater because we’re building it in the dry.”

Reclaiming export ground

As BAE Systems works through its batch of eight frigates for the Royal Navy, international orders may soon follow. Norway is actively considering the Type 26 design, and discussions with the UK government are said to be well advanced.

“There have been intensive discussions since that MOU [Memorandum of Understanding] between the UK Government and the Norwegian Government,” said Lister. “Those negotiations are largely concluded and the Norwegian government is entering a decision-making phase, looking at the results of those discussions with the four bidders before making a decision sometime later this year.”

He confirmed that if Norway selects the Type 26, it would “interleave” with UK builds from Ship 4 onwards. “Because the ships are so similar—or frankly, identical—this brings with it the possibility of taking the efficiency up and the cost down.”

If confirmed, it would mark the first major warship export from the Clyde in decades. “We haven’t built warships for export for some time. If they do come in our direction, we’d be very, very pleased.”

Built strong, built to last

Each Type 26 will have a design life of 30 years, but Lister suggested they could serve even longer. “They’re built strong—built stronger than the Type 23.” Fully loaded, each weighs just shy of 8,000 tonnes. “That’s a big ship,” he added.

The design’s roots are anti-submarine warfare in the North Atlantic, and its form follows function. “The basic requirement of the Type 26 is to hold a Russian submarine at risk in the North Atlantic. That means the commanding officer of a Russian submarine is always in doubt if he knows that there’s a Type 26 deployed in the area.”

Key to this are stealth and detection. “Every piece of equipment that makes noise has either been designed out or designed to operate quietly,” he said. Pumps, engines, and fans are tested and installed to minimise acoustic transfer to the hull. “We’ve brought the disciplines of building a nuclear submarine into this ship.”

The ship’s modular mission bay allows it to adapt to future warfare needs. “Today it’s drones. Tomorrow it could be electronic warfare–equipped drones. Then hypersonic missiles. Whatever it is, this mission bay is designed to take that capability to sea.”

A digital yard for a digital ship

This leap in capability is made possible by a digital overhaul of the yard itself. “What we’ve done is take the shipyard digital,” said Lister. Workers now use ruggedised laptops on the shop floor instead of paper drawings. “We wanted to communicate the design of the ship digitally. It’s one thing for the designers to have this model—but now everyone on the shop floor has access to it.”

The transformation extends from fabrication to fit-out. “We’ve modernised the panel line at a cost of just shy of £20 million. It produces panels at twice the rate of the original manual line. Our operators are much safer. Welding is intrinsically dangerous—we’ve removed the person from the hazard as much as we possibly can.”

That same digital thinking continues after the ships go to sea. “We run a team that is in constant connection with the operational fleet. The availability of the combat management system is absolutely up there—right up at 98 percent.”

Lister compared it to real-time telemetry. “It’s not the same as Formula One, but there’s a version of that happening in real time with the deployed fleet.”

UK supply chain, but not UK steel

Despite the UK setting steel procurement expectations, the Type 26 programme has largely sourced its steel abroad. “The British steel mills were invited to tender. They chose not to,” said Lister. “The grade of steel that we require is high strength and in plate thicknesses that aren’t a standard output for British steel mills. So it’s sourced from Sweden, mainly, and some Dutch.”

Still, he stressed that the value-added component of the ship is overwhelmingly British. “The engines, the computing network, the stabilisers, the rudders, the valves—every valve on board is just being sourced from a supplier in the UK. The equipment comprises 55 percent of the ship’s cost.”

Looking forward

BAE Systems expects to deliver Type 26 frigates annually by the time Ship 5 enters production. “That’s the objective,” said Lister. “The ambition in all of this is to build a warship every year—and to build them well.”

As foreign navies look closely at the Type 26, Lister sees a strategic opportunity for Britain to reassert its presence in global naval shipbuilding. “The SDR [Strategic Defence Review] was a very clear endorsement of this requirement and of shipbuilding in Glasgow. It was brilliant to see the Prime Minister announce that here in Janet Harvey Hall.”

For now, BAE’s focus remains on keeping pace. “The Navy wants us to build these ships as quickly as we can. That’s the cheapest way to build the ship: in the right order, at the highest pace you can safely achieve—maintaining quality all the time.”

Aiming to build the 4th Type 26 in 66 months. Five and a half years! Still can’t get my head around modern shipbuilding timescales.

A quick wiki check on the type 45 reveals just over 6 years for the type 45 destroyers first steel cut to commissioning.. I’d imagine without a regular beat of orders and a much reduced fleet size, then both Rosyth and the Clyde yards will be dependant on export orders for their long term survival…

Not good when you compare how quick other European navies turn out their ships.

How did the Danish Iver Huitfeldt-class took 3 years from keel to in service. One small problem it didn’t work

😂

Good point

Just UK shipbuilding tbh, because its so small scale. Look at some of the yards doing commercial vessels in korea/china, they just print them out basically

“Aiming to build the 4th Type 26 in 66 months. Five and a half years! Still can’t get my head around modern shipbuilding timescales.”

That is not modern building timescale , it is UK building timescale.

Good news from Bae. Anything to speed up production is welcome.

Would it not be worth, given the increasing defence budget, as well as keeping econemies of scale in mind, ordering more? Given the geopolitical tension that’s arising and the gov saying we need to be on a war footing, wouldnt this make sense? Cost per ship would be lower, and we’d have more vessels in the water/in reserve for when others have issues or God forbid, be sunk

A combat management system availability of 98% doesn’t sound very good to me. I worked in the electricity supply industry and 99% availability was considered as an abject failure, success was more like 99.99% availability across all customers and 99.5% availability for the worst served customers.

In the world of IT with a mission critical system 98% is horrendous. We generally work to an availability of 99.995% but that means having multiple computer rooms and an active, active cluster. It can be as high as 99.999% availability if it really is safety critical which I would suggest the CMS on a warship absolutely is.

Intergration is very difficult. You have various systems written in different languages to different risk management programmes and then you have to write code to get the whole lot to talk to each other. The big issue is that there isn’t an ISO standard for software development in warships. Aircraft have a whole set of development standards requiring risks up to certain level to be mitigated.

Nobody dies of hard work at BAe

But they all die nonetheless.

Its a pity they utterly failed to deliver the type 26 programme at pace, precision and purpose it was lethargy, excessive cost and bloated bureaucracy.

Now they are sniffing the wind thinking Norway and the RN are about to pour money down their throats, suddenly they are pretending to be efficient ship builders- someone please remind them they’ve taken since construction began in 2017 until now (8 years later) to get first of class into the water to begin fitting out.

The MOD set the pace of the Type 26 Programme,not BAE,why keep repeating the nonsense that has been debunked on here ad nauseum ?.

The fact that the weapons industries are such wealth creators for the top 1% is a joke! Public money is funnelled to theses Military Industrial Complex CEO’s share holders and owners, at a time we cannot defend our borders from the invasion of the migrants, who will end up in the employ of these massive corporations via a yet to be installed fast track system. In order to turn the 3rd world invaders into Tax paying minions working hard to produce the weapons of mass destruction! At a reduced rate compared to the previous indigenous work force, of course?.

All to keep producing the British weapons that the out of control World needs.

All while neglecting to stop the small boat invasion of of our southern border, that is a 30 mile wide Moat at its narrowest part. Yet the the Government tells us the massive increase in defence spending is to keep us safe, while ignoring the small boats?

Remember that if it was not for small boats on D-Day we may be speaking another language, so why do our government ignore today’s small boats?

History has proved the effectiveness of small boats 06/06/1944. When an army was returned by them.

You may find,getting employed by Bae isn’t that easy,so unskilled migrants have zero chance. Have a go and tell us how you fare.

We now live in a two tiered system, and what the lunatic left want the lunatic left get! Do you live under a bridge? The boat people are all Doctors and engineers, keep up!

Fair point 😅

A lot of positivity there. Modernisation and efficiency are always great to hear about.

But I always fall back to the same feeling. The key to a successful Naval ship building industry is a successful civilian ship building industry. I feel every £ invested into making the UK civilian ship building industry competitive would be repaid in full from economic growth and savings on naval projects.

For every £ invested,look how much of the high wages ends up back in the goverment coffers. Baffling how government’s don’t grasp this.

Who knows. Maybe they’ll even master handing the RN working ships on time and to budget…… but I won’t hold my breath.