Scottish Labour MSP Paul Sweeney has pressed ministers to ensure that steel from Scotland is used in the landmark deal to build five Type 26 frigates for Norway.

Speaking at Holyrood, Sweeney said: “Scotland—by which I mean Glasgow—has won the biggest shipbuilding export order in this country’s history, with five Type 26 frigates going to Norway. However, the frustration is that, as it currently stands, no Scottish steel plate will be able to be supplied to that programme unless we can get Dalzell back up and running. Will the minister give an assurance that he will do all that he can to get it back up and running, so that we can get steel plate from Scotland into those fantastic Scottish frigates?”

Responding, Business Minister Ivan McKee said the government was committed to supporting the Dalzell site. “I give that assurance. As I have said, we have been working extensively with GFG on the potential for new orders. I have also indicated that there were maritime orders in the pipeline, and we will be able to give more information on that in the near future,” he told MSPs.

McKee added that the site remained operational only due to government intervention. “We will continue to work with the owners to look for other opportunities to get the plant back up and running, but it is worth recognising that it is only through the work of the Scottish Government and Scottish Enterprise that the plant is still capable of fulfilling those orders, as it has been supported through this period of time.”

The exchange followed Sunday’s announcement of the £10 billion contract for Norway to acquire BAE Systems’ Type 26 anti-submarine frigates, which will be built on the Clyde.

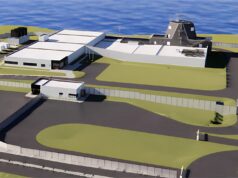

The UK Government and BAE Systems have secured more work for Glasgow’s shipyards after Norway confirmed it will buy the Type 26 frigate, with the Clyde set to play a central role in the programme.

Deliveries to the Royal Norwegian Navy are expected to begin in 2030, tying the future of Scottish shipbuilding more closely into NATO’s northern defence.

The Clyde is already busy turning out the Royal Navy’s eight Type 26s, with the first three ordered in 2017 and a further five added in a £4.2 billion deal signed in 2022. That contract underpins about 1,700 jobs directly at the Govan and Scotstoun yards, with another 2,300 spread through the wider UK supply chain. BAE has also poured more than £300 million into upgrading the facilities to keep the line moving for the next decade.

“It is good news for the Clyde. Securing this work gives us confidence for the future and keeps skilled jobs here in Glasgow,” one yard worker told UK Defence Journal.

Norway is expected to order at least five frigates, enough to replace its four surviving Fridtjof Nansen-class ships and rebuild the numbers lost after the sinking of HNoMS Helge Ingstad in 2018. If confirmed, the deal would make the Clyde the construction hub for more than twenty Type 26s worldwide, counting ships already committed for Britain, Australia and Canada.

The impact reaches beyond BAE. Ferguson Marine, further downriver at Port Glasgow, has already won work on the programme, fabricating structural modules for the fourth Royal Navy ship, HMS Birmingham. For a yard that has struggled in recent years, these contracts provide a lifeline and show how the Type 26 supply chain is spreading benefits across Scotland.

Economically, the numbers are significant. Defence spending on frigates alone is estimated to support more than 12,000 jobs in Scotland when supply chains are factored in. Every major contract brings a multiplier effect across the region, from steel cutting to advanced electronics, reinforcing the Clyde’s place as one of the UK’s most important industrial clusters.

The Norwegian decision also has a strategic dimension. By joining the Type 26 community alongside the UK, Canada and Australia, Oslo ties itself into a long-term multinational programme with shared training, maintenance and upgrades. For the Clyde, it means the yard is now building ships not just for the Royal Navy, but for NATO allies facing the same threats in the North Atlantic and High North.

With the order book stretching well into the 2030s, Glasgow’s yards are secured as the heart of Britain’s advanced warship production, a position strengthened rather than threatened by the internationalisation of the programme.

Whilst it is good news the reason we are winning is that it isn’t feeding a massive feather bedded WorkFare scheme and we are being competitive in sourcing.

So be very careful what you wish for in terms of supply chain.

MOD budget is stretched enough without taking on other problems – as that would be The Starmer touch to just take the money to subsidise steel out of defence.

Exactly, I want to build and export the best warships in the world at a reasonable price. The best way to do that is to make sure we get the best inputs. We should buy the best steel (domestically or from allies) for the job.

We are a small island, we will never be able to produce every component for something as complicated as a warship and the tiny amount of steel being used will have zero impact on our domestic steel industry.

We need to move on from this 20th century obsession with processed iron alloys, it’s not longer a very important industry.

For an island nation that needs ships for its defence and trade the idea that steel for shipbuilding is not important shows how blind we have become to our real and unchanged vulnerabilities. Anything over, under or sailing on the sea is of crucial importance to the U.K. and this extends way beyond our home waters.

Steel is still a critical component in all national infrastructure including railways, all news buildings and of course military equipment. The ability to manufacture as many of the numerous grades required is therefore a critical national requirement, which even our mainstream political parties seemed to have realised.

It is not a 20th century obsession but what is dangerous is our politicians wish to achieve net zero at the expense of all our remaining heavy industries because no other country in Europe is deliberately self harming their economy and by that it’s defence capability in this way.

The important thing is to retain a viable U.K. including Scottish steel making industry and building ships for export is an opportunity to perhaps grow and sustain this critical industry.

Meanwhile in the real world, specialist steel requires elements that dont physical exist in the country. The idea that there’s a magic wand that you can wave and not be dependent on imports is just plain silly. During the largest war in human history the UK built 1000s of aircraft from imported Aluminium ore. There is no ore in the country and yet that didn’t stop production.

Your half baked put down would have been ok if I had suggested the UK should be totally self sufficient in steel production but I clearly didn’t. The article was explicit about a particular steel plant whereas I was making a more general point about sustaining and if possible growing the U.K. industry.

Oh for goodness sake. It doesn’t matter where the plant is the UK its still dependent on imports. The purpose of defence spending is to defend the country not to provide never ending amounts of taxpayers money to subsidise uneconomic steel production.

Spoken like a true free marketeer. I suppose you would have allowed Sheffield Forgemasters to go to the wall. Even the Tory’s were not that daft and have supported keeping U.K. virgin steel production. It is a strategic industry for national infrastructure and defence whatever you or I think.

Is it uneconomic? If so, why is it economic? And if it is taxpayers money, how much tax payer claw back so you get from this plate mill being in the UK? Plate is a central material in building ships and it is centrally important we use British plate and invest in modern facilities. Nearly all the steel, plate section and tube for the super carriers came from the UI nearly all from Appleby -Frodingham, now closed due to lack of vision. All the great and non great ships built in this Country came from plate made in this Country. We have only Spartan UK (that take slab from abroad for some reason), Cumbaslang, Dalzall and there are recent reports on the need for new plate facilities in the UK. Buying from abroad denies tax and we cannot afford to buy from abroad anymore anyhow as we are broke! To have a few very efficient shipbuilding industry, all the main materials need to come from within!

And we must retain the ability to make 15 inch guns as well,

Are you at all worried about the UK ability to make carbon composite fibre for aircraft? Do you think we should also be mining iron ore in the UK? If not then what’s the point in making steel? It’s just one small part of a lengthy supply chain.

In reality steel is an issue for the UK because.

1) we don’t have the market to maintain steel making across all grades of steel.

2) we don’t have the raw materials to maintain virgin steel production and so needs to import coke and ore.. leaving UK steel open to international price fluctuations or in the case of war loss of shipping capacity.

That really leaves the UK in a bit of a bind to be hones.. that is why it’s actually probably better to have Electric Arc Furnace steel production in the UK as we have a lot of scrap steel and just keep one basic oxygen furnace site running for critical domestic virgin steel needs.

UK Industrial electricity prices in 2023 were 46% higher than the average of the 32 members of the International Energy Agency, a group that includes EU and G7 nations that, between them, account for 75% of global demand. Our suicidal dash to net zero means we are sacrificing our very limited heavy industries that remain because they are at a severe disadvantage even compared to similar European nations.

The Government is trying to address this with some help to industry and encouraging modernisation but this can only go so far and the fundamentally stupid level of wholesale electric prices needs to be brought down in the U.K. For steel that could make a huge difference, encouraging investment and further modernisation that is desperately needed. The demand for various grades of steel in the U.K. is still significant and a good part if it could be supplied by our own ‘small’ industry.

And just how to do you intend to out compete Swedish steel production when Swedish Iron ore is the best quality in the world and when hydro electric plants provide cheap electricity. Theres no magic wand that magically makes low value added manufacturing with imported materials economically viable.

Interestingly our electric prices are a bit of an artefact caused by liquid gas imports. Essentially the price is set by the most expensive component of the generating mix on that day and it’s always imported liquid gas as that is around 40-50p per KW where as most other types of generation are at 15-20p per KW.. but even if .1% of our electricity is generated through liquid gas in a day, that days electricity wholesale price is set on the international Liquid gas price….. it’s a bonkers system which means our producers have been utterly canning profits in what is essentially a price gouging system.. if we set our whole sale price to say the average cost of electricity production in a day we would generally have some of the cheapest electricity around.. as our renewables are actually cheaper power generation than a gas fired or nuclear generated power.

I agree, we can actually bring down electricity prices for industry massively by tying them to intermittent renewables. We can use excess energy to make steel, aluminium and hydrogen via electrolysis and simply switch if the process in periods of low wind that way preventing us from making wasteful payments to wind operators to switch off and minimising our use of expensive LNG.

Electricity prices fluctuate in *both* directions (sometimes they are even negative) and don’t forget, that (unlike blast furnaces) electric arc furnaces can be switched on and off as required, creating an opportunity for a canny operator to work the duck curve, and thus benefit from much reduced energy costs.

Tata would not be investing a billion pounds of their own money in UK steel if they thought UK energy costs were too high.

The real spike in energy prices came about from about 2020 as the impact of net zero policies and wars started to have an impact. Much of the valued added steel products produced by Tata we use in construction went up by a huge percentage during this period.

Tata are factoring into their investment plans that the U.K. Government is reducing energy prices by 25% for much of our heavy industry from 2027 because without it U.K. steel production of virtually any kind is finished.

For a perspective the ONS reported a 46% drop in U.K. production of basic metals and castings as a result of our high energy prices during this period. However, well you use electric arc furnaces if your electricity price are 30% higher than your European competitors then you are going bust it is that stark.

I’m not sure what wholesale electricity prices had to do with the viability of Port Talbot’s blast furnaces, which produced their own gas (for reaheat and electricity production) from coal.

Tata made a commercial decision to move to EAF long before the government got involved

The spike came because wholesale liquid gas prices went through the roof.. an because of an idiot issue with how we set the wholesale price of electricity out electric prices went up in line with liquid gas prices.. because the price of electricity in the UK is set on the most expensive product method used that day.. even if it’s only 1% of the power generated in that way.. the simple fact is net zero has very to no impact on wholesale electricity price in the UK and everything to do with how we link our price to liquid gas imports.

funny how the nation can find vast amounts of money for enhancing the yards yet the decline of steelmaking all across the country has been allowed to wither in the Vine for decade’s under privatisation and sales to companies like Tata it’s very good to see that the industry’s

lack of production capacity has finally been recognised and the industry can be restructured and it’s capacity increased.

The winning of export orders for the T26 and T31, and the national shipbuilding strategy in general, means it is imperative that we also produce our own steel of the right grade.

We also may need the facilities in case of an impending war. I am totally dumbfounded how the lessons of being an island during the time of war have been forgotten.

Might I revise that for you.

Ang war that comes won’t allow time to build a fleet as in ‘82 we fight with what we have that can be rapidly upgraded.

Which is why ordering more T31+ is urgently needed preferably with Mk41 fitted – having hulls that are built or in an advanced state of build is what makes a difference.

Whilst in time of war a five year build can probably be shortened to 18 months a conflict will be over before that.

It’s the long lead time items that really bring everyone unstuck. UK idiot practice (caused by clueless Treasury rules) vastly increases the risk. Yesterday’s radar or gun might not be the best, but if it’s still in the shed, that fast build frigate might make it to sea in a usable state before the war ends.

To be honest there is a significant option out there now around the next war not being over in less than 18months.

Essentially china if it goes to war has zero intention of fighting a short war as it knows the west has a profound ability to concentrate forces and fight a short set piece campaign.. China has no intention of fighting that war. Because it also knows the west has no stomach for the long drawn out war. China if it decides to fight is planning to throw the world into a long drawn out bloody and economically destructive war of suffering over many many years.. because it thinks that is how it will beat the US. It knows there is a pretty good chance that on balance it may loss the first major campaign in any sino US war . It’s essentially build an entire navy to be sunk in an attempt to land a crippling blow to the USN.. because it knows if the USN losses 50 major surface combatants it’s shattered and will take 30 years + to recover the PLAN losses 50 major surface combatants, it’s still got 90 left and has 25 in the middle of building and can completely replace its losses in 4-5 years… essentially China is building a war machine and social construction to loss for the First year or so then simply out produce, out suffer and out last the west.

Set against decimation of their shipyards? Or is there a war game where both sides keep shipbuilding and building missiles whilst slugging it out.

The bit I do not get is that the Chinese economy is absolutely predicated to exporting mountains of stuff to the west. So in a long war how is their mess of an economy with a big property bubble that still isn’t under control going to survive?

At the present rate two shipyards in the UK are going to be outbuilding the USA on the frigate front. Some years we are going to be launching 4-5 new ships with all these export orders rattling around as they will be built to commercial pace and not to in year budget pace.

Huge investments have been made in UK shipbuilding productivity and labor saving e.g. robot cutting and welding. So the the two main yards, assisted by others elsewhere, have plenty potential to grow output, they just need the orders.

Besides the economic implications, I don’t realistically see China out-producing the whole of NATO (which has numerous very competent producers) in *credible* warships any time soon. If you add in Japan and South Korea, the idea is preposterous.

I would frankly be much more concerned about things like availability of semiconductors and higher end metals.

The CCP will no doubt have studied all this and will act accordingly.

Huge investments have been made in UK shipbuilding productivity and labor saving e.g. robot cutting and welding. So the the two main yards, assisted by others elsewhere, have plenty potential to grow output, they just need the orders.

Besides the economic implications, I don’t realistically see China out-producing the whole of NATO (which has numerous very competent producers) in *credible* warships any time soon. If you add in Japan and South Korea, the idea is preposterous.

I would frankly be much more concerned about things like availability of semiconductors and higher end metals.

The CCP will have studied all this and will likely act accordingly

Have you read this?

In the last two decades, China has ramped up investment in shipbuilding. And that has paid off: more than 60% of the world’s orders this year have gone to Chinese shipyards. Put simply, China is building more ships than any other country because it can do it faster than anyone else.

“The scale is extraordinary… in many ways eye-watering,” says Nick Childs, a maritime expert with the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. “The Chinese shipbuilding capacity is something like 200 times overall that of the United States.”

We might have a quality advantage but there electric cars are now overtaking western designs so how long before they do with military equipment.

They are building millions of tons of bulk ships- huge empty boxes. Albeit they outperform in things like batteries, China’s car industry was accelerated using stolen German IP. OTOH Their Mil tech is mostly based on Russian junk, and despite ripping off Airbus, they still can’t build competitive Airplanes. They have a lot of catching up to do.

As Johnathan has rightly pointed out the Chinese are playing the long game and our politicians still can’t decide if they are a threat.

Whilst the US might still be militarily number one this century is going to see a huge shift in power from west to east and the US cannot do a lot about it.

You have to remember that underneath the Chinese “capitalist” market economy is essentially a state controlled communist economy ready and willing to take over. Their entire economic system is a capitalist overlay and all the structures are in place to simply remove that market economy overlay and convert their entire system to a state controlled system. Every company has a communist party shadow board ready to take control… it works because the western capitalist system simply cannot conceive that what seems like a normal free market business is at its foundation not.

So to answer the question how would the Chinese economy survive a war in its present state.. the answer is it would not, it would become a centralised and controlled wartime economy.. at the swish of a pen ( it’s all imbedded in Chinese law).

China has squandered a vast fortune in lost growth to construct their economy this way, one expert in the field estimates they have lost between 1-2% of growth every year for around a decade to sculp and harden their economy ready to turn it into a wartime economy. To put that in perspective some experts feel it’s likely China may have sacrificed up to 800 billion in lost growth just in 2025 due to war planning its economy.

What will truly turn this into a long drawn out war is essentially the sheer mass of the combatant nations in people resources, money and industry.. you say is it a war game in which both sides keep producing while slugging it out and the answer is yes that is exactly what will happen. We are talking about to continental size enemies 10,000kms apart.. all they can do is hurl pain at each other until one gives up and concedes or chooses suicide by nuclear fire.

And if anyone thinks the Chinese people will not let this happen they really don’t understand where China is at present.. you have a Nationalist communist government leading a country of mainly Han exceptionalists ( think communist state with all the best bits of the third Reich added on for good measure). Who all believe that Chinese destiny ( to reunite and become the hegemonic world power) can only be achieved by their own suffering, and this is the country that lost 40 million people to a social experiment, the reaction to which can be summed up as “maybe it was not that good an idea after all.. but worth a shot”

And for those who are not signed up.. you have 100 million CCP members watching them, a 5 million strong internal security force and more monitoring than the rest of the planet put together.

All lead by a leader who has absolute control ( he personally directly controls all state security bodies and armed forces as well as the executive of the communist party and its committee), who just happens to be essentially a brainwashed CCP supporting Han exceptionalist himself ( he was arrested and put into hard labour/political reeducation.. and after that climbed to lead the CCP) who is also very clever and is ( I quote the US naval war college ) the greatest living maritime leader in the modern world and one of the greatest of the modern age.

When China goes to war it will just keep going and going and going.. that is literally their doctrine.

The Mao papers “ on protracted war” are literally considered the standard primer for members of the PLA.

I get the political issues but SB made the fundamental point. All war is economic and China has a highly export dependent economy. They are not a major Petro-State like Russia, who can slog it out because the world still needs their energy.

Where do they export to ? And what happens to those nations economies when China stops exporting ?

A US sino war will be a total war.. a both nations will turn their production to wartime production, global trade will collapse. It will be production access to resources and economic reserves as well as political and population will that will matter… because neither the US or China can be knocked out of a war simply by overwhelming force. as I said China has been burning untold trillions of dollars on hardened its economy ready to flip the switch to a wartime economy to turn it into a wartime economy, the west has not.. it’s also started to hide everything it can, it no longer publishes Mineral usage reports because everyone is pretty sure its stockpiling strategic reserves like a mad thing.

The final simple truth.. the side that wins tends to dominate the maritime environment.. China has around 260 times the shipbuilding capacity of the US and operates 20% of the worlds merchant fleet.. and if you own the seas you eventually win… ask Hitler, as imperial Japan, ask the soviet union and even Napoleon.

But the issue is even if the west wins its economies will be shattered because our modern economic model cannot manage years and years of total war, with the nation that produces a huge portion of our actual stuff.

Unfortunately Mr Sweeney is some 30/35 years too late in looking for a Scottish steel industry…. Even UK produced steel would be very difficult to do now…

Your half baked put down would have been ok if I had suggested the UK should be totally self sufficient in steel production but I didn’t.

I think that expecting steel work to all be done in the UK is overlooking the detail of the deal. Much of the basic steel work construction may well be done in Norwegian yards with Swedish low carbon dioxide emission steel. Blocks brought to Scotland to assemble and fit out. Currently only the composite mats are coming from Norway that is no where near enough to satisfy the requirements for Norwegian content.

I agree that some sub assemblies for T26 might well be built in Norway.

Bear in mind that they don’t have a lot of large yard function there but they do have a decent skill level with what they have which is very geared to the oil industry.

As ever it is a cost/benefit/risk analysis. The more convoluted the supply chains the bigger the risks of timelines and of QA. BAE won’t want a lot of risk in a tight build timeline.

Surely, there must now be a case for at least another ‘big shed’ to allow parallel construction of these big orders – before the RN has to delay its delivery schedule or foreign yards get orders because of delivery slots being so far in the future?

It will take time of course to recruit Nd train the necessary workforce needed.

Scotland has designed and built a great frigate there with no help from the British, apparently.

“construction hub for more than twenty Type 26s worldwide”.. I’ve seen this(and/or words to this effect) in a few posts.. are Canada and Australia not building their T26 versions in their respective countries?