Three more F-35B aircraft have been delivered to the UK, bringing the fleet to 24 aircraft.

The aircraft flown from Texas to RAF Marham by 207 Squadron and assisted in crossing the Atlantic by a Voyager tanker.

Lightning strikes at Marham, with three new aircraft joining the UK's Lightning Fleet. ⚡

Find out how we support F-35 at @RAF_Marham as part of Lightning Team UK ⚡https://t.co/qigjzZoOdhPhoto credit, to LAC Natalie Adams @RAFPhotog #LTUK #Lightning pic.twitter.com/IJoxGXWgcV

— BAE Systems Air (@BAESystemsAir) October 29, 2021

Six more jets will arrive in 2022 and seven more will arrive in 2023 with an expectation that all of the 48 in the first batch will be delivered by the end of 2025.

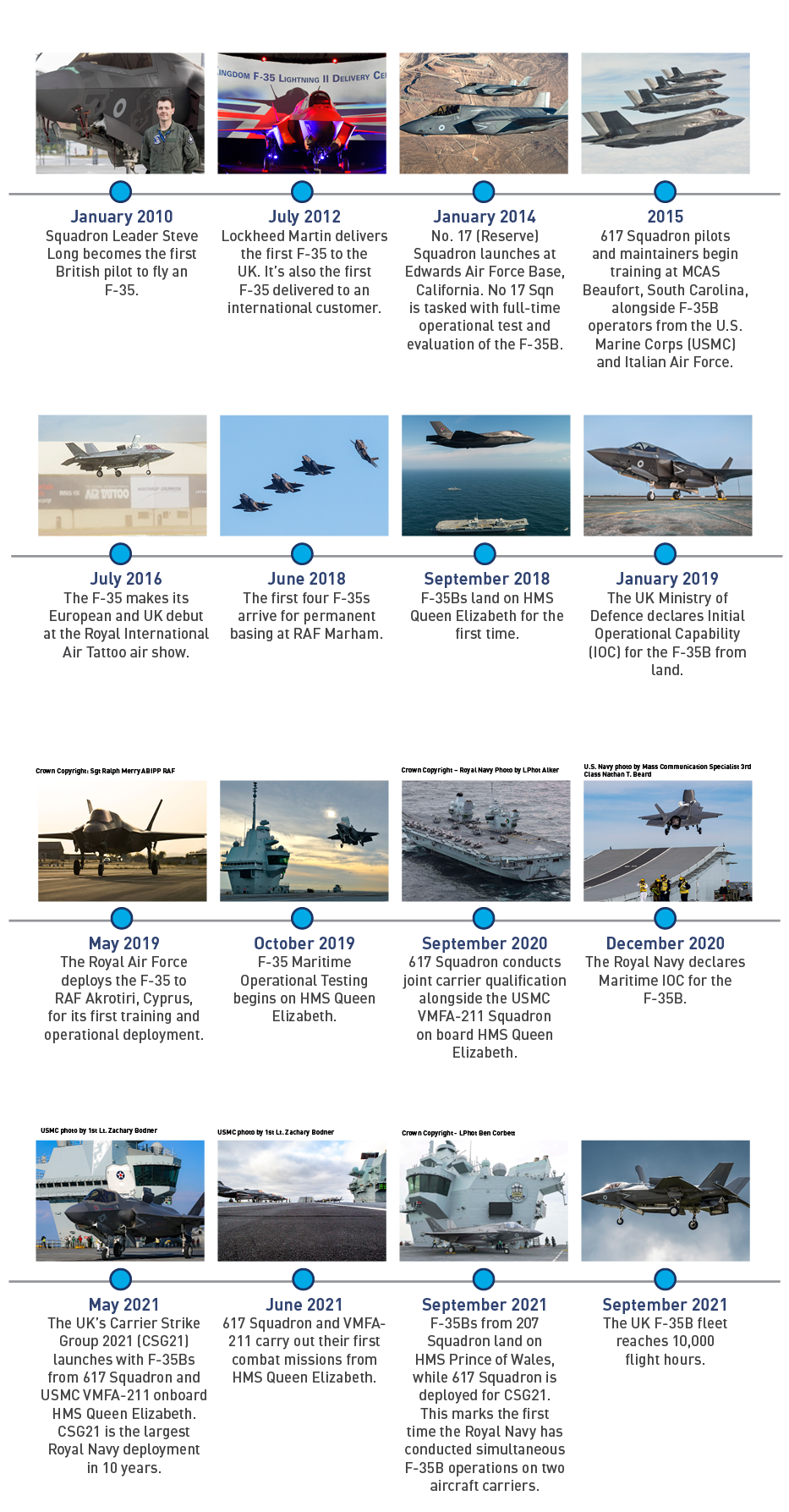

Since the delivery of the first jet in 2012, the United Kingdom F-35 programme has expanded tremendously.

Recently, the UK fleet reached a new milestone, when it crossed the threshold of 10,000 flight hours. This milestone has been nearly 10 years in the making.

In 2012, the first F-35B was delivered to the UK. Currently 24 of the planned first batch of 48 aircraft designated for the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy are operating as three squadrons in two locations: the 617 ‘Dambusters’ Squadron and 207 Operational Conversion Unit Squadron at Royal Air Force Marham and the 17R Test and Evaluation Squadron at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

Here’s a look back at some of the programme’s most significant milestones over the years.

Excellent stuff.

Just don’t tell our Nigel! 😉😆

😂 The RAF’s version of Ajax 😂

How many of the current 24 did not meet durability testing with a life cycle of only 2000 hrs?

Not forgetting Meteor and Spear Cap 3 in 2028 of course.

Time for dinner I’ve been told, more to come later!

😆 now now mate, comparing to Ajax is a very low blow, even from your good self.

Enjoy din dins.

Very true, but so is this!

Do you happen to know our Lot breakdown?

“Static Structural and Durability Testing • The program secured funding and contracted to procure another F-35B ground test article, which will have a redesigned wing-carry-through structure that is production representative of Lot 9 and later F-35B aircraft.

Testing of this production-representative ground test article will allow the program to certify the life of F-35B design improvements. The production and delivery dates are still to be determined.”

Can you begin to imagine trying to sort out this mess? I have and when you start to add different requirements for different customers, the problem simply becomes even more unmanageable.

Think UK missile requirements vs US requirements and the impact that will have alone, then add Block 4 into the equation.

Fix one problem cause more elsewhere. And it’s already happening.

“In March 2005 we reported that the F-35 program had started development without adequate knowledge of the aircraft’s critical technologies or a solid design.

12 Further, we reported that DOD’s acquisition strategy called for high levels of concurrency between development and production—an approach that runs counter to best practices for major defense acquisition programs.

In our prior work, we identified the F-35 program’s lack of adequate technical knowledge and high levels of concurrency as the major drivers of the program’s significant cost and schedule growth, and as well as other performance shortfalls.

13 The high levels of concurrency have also made it difficult to sustain the fielded aircraft.

In April 2019 we found that as aircraft, spare parts, and mission software continued to be developed and updated for the program, aircraft in the field had at least 39 different part combinations, thereby posing aircraft sustainment challenges.

Furthermore, DOD’s training and operational squadrons were flying F-35 aircraft with three different blocks of mission software—2B, 3i, and 3F—with each block providing different capabilities and requiring unique sustainment needs.”

https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-439.pdf

But there’s probably not a fighter program in history that’s not had issues. Our own Typhoon T1s were limit to air to air and we’re retiring them early. Typhoon development has been glacial and there’s been quality issue along the way. Not saying the Typhoons bad but just as a case in point that most fast jet programs have problems so the F35 is not unique it was just a bigger more ambitious program.

https://www.defensenews.com/air/2015/10/13/germany-suspends-eurofighter-deliveries-due-to-quality-problems/

Things have moved on since 1995 and for the better.

Note the reference to carrier operations, I wonder what’s in the pipeline?

https://www.key.aero/article/team-tempest-takes-new-approach

There’s more to come it would appear?

“The Eurofighter Typhoon will receive many of the innovations first, as Team Tempest sees the aircraft’s technologies, sensor and human-machine interface synergies as one that could serve the programme best.”

https://defence.nridigital.com/global_defence_technology_sep21/team_tempest_fcas

2015

“The German Air Force has temporarily suspended delivery”

2020 has now ordered 38 Tranche 4

Hi Nigel. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with the Typhoon, I’mquite please with recentprogress. Just that fast jet programs are complex. The F35 gets a lot of bad press but for what the UK want its will perform far better than the Harrier its replaced. Again the Harrier wasn’t bad its just a generation behind. Going back to the F35 its winning every procurement competition against 4+ gen fighters. So when airforces are looking at it they’re clearly seeing something they like and they have far more data than us or the press.

I see what you’re saying.

From my perspective, It’s the only game in town unless we opt for Russian or Chinese 5th gen aircraft which have now caught up with the west.

The F35 was supposed to keep us ahead of them until the arrival of 6th gen aircraft but has failed to deliver what was promised at the time and will not be able to do so until 2030 when the 6th gen prototypes will be flying.

Next year will be the moment when the USA decides which way it will spend the lions share of its defence budget on one F-35, or two, funding its sixth-gen fleet along with a replacement for their ageing F16 fleet which the F-35 was supposed to replace.

Not sure if you had the opportunity to read my link, but the request for “availability of electromagnetic catapult and arrestor wire systems to launch aircraft” from a ship” within the next three to five years suggests to me that at some point we might just see an unmanned Tempest flying from the carriers?

Worth reading.

14th April 2021

FEATURE

In this exclusive look behind the scenes of Britain’s new Future Combat Air System, Jon Lake gets under the skin of an aircraft due to enter service in just 14 years’ time, and yet its configuration is still undecided.

Tempest will be a ‘system of systems’ with a manned (or optionally manned) fighter aircraft at its heart – the final design, however, may differ substantially from the configuration featured in BAE Systems’ marketing effort

The Tempest name refers to a planned new fighter aircraft expected to sit at the heart of what will be a ‘system of systems’, consisting of crewed and uncrewed platforms, weapons, sensors and other force elements. That ‘system of systems’ is also called Tempest, and to add to the risk of confusion, the UK industry team working on this whole Future Combat Air System (FCAS) is known as Team Tempest.

The aerospace industry has long been somewhat platform-centric, based around the development and production of a particular aircraft type. In more recent times, those aircraft types have been ‘weapons systems’, and the sensors and fire control systems they carry have become progressively more important. Those systems are today at least as significant as the airframe and powerplant, but the aerospace industry has continued to focus on building individual platforms.

The product has always tended to be a standalone platform, albeit one equipped with important sensors, systems and weapons. By contrast, the new FCAS, rather than being a single standalone platform, will be a connected network of capabilities, hence a ‘system of systems’.

This new approach is required because air forces are facing a very complex and dangerous threat environment that is changing rapidly, and one that is proliferating around the world. Technology (and especially threat technology) is changing so rapidly that the framework of the new FCAS needs to be extremely adaptable, responsive and upgradable.

Leonardo’s director of major air programmes, Andrew Howard, told AIR International that “the future of air operations will not be about groups of individual aircraft flying individual missions in a warfighting posture. It will be about rapid and large-scale information exchange across a network of distributed capabilities, on an almost constant basis, within the air domain, and across all other domains, such as land, sea and space.

This ‘system of systems’ model underpins the Tempest concept and requires a completely new approach.”

Elements and categories

The core element is “likely to be a manned or optionally manned system but there will be a number of other systems or components that sit around it,” said Michael Christie, BAE Systems’ director of future combat air systems, and the company’s senior representative on Team Tempest. Christie defines these elements according to four broad categories. As well as the first, the core platform, there are what he calls adjuncts, a more generic term for the loyal wingman/remote carrier unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs) that will also be developed.

These could have a range of different capabilities, and could even fulfil different roles.

The third category refers to ‘effectors’, a term Team

Tempest prefers to ‘weapons’ because they may not deliver kinetic effects. The final category is command, control and communications.

A radical approach

The UK-led FCAS and the next-generation Tempest aircraft at its core are being developed in a radically new way, and this can make the programme difficult to understand and to follow. Judged by conventional metrics, the programme might appear to be lagging behind rival US and Franco-German-Spanish efforts to develop new-generation combat aircraft and combat air systems, for example, but to make that assumption would be a mistake.

Although Team Tempest is looking to produce a flexible, affordable combat aircraft that reaches the market in the 2030s, the team is in no rush to get an aircraft into the air or even to lock down the design.

Development of Tempest is proceeding apace, but there are few obvious milestones or markers of progress since a key feature of the programme is that it is quite deliberately concentrating on developing and maturing the technologies and capabilities required. Platform development will be compressed and left until the last moment, thanks to extensive and indeed unparalleled use of model-based systems engineering and design.

Quite simply, this is because, as Andrew Kennedy, head of group strategy, BAE Systems Air, observed: “The sooner you lock down the design, the sooner it’s obsolete!”

Michael Christie acknowledged that this approach means that “some people are nervous – it feels like you’re not firming things up until later, and that’s partly true, but what you also get from it is much greater maturity, much greater understanding of the system and how it works, so that you don’t spend the period taking a requirement and translating it into a product, trying to work out what the requirement really means.”

Leonardo’s Andrew Howard gave more details: “Traditionally, the capabilities we could bring to the battlespace were restricted at an early stage by the decisions made in designing a platform. An aircraft would be designed and built, and then companies like Leonardo would work to equip it with useful technology. If you wanted a specific capability, but it wouldn’t fit on the aircraft, then straight away you’ve got a costly and time-consuming problem to solve. We, as Team Tempest, have recognised that this model is no longer fit for purpose.”

What this all means is that although the US NGAD programme already has a flying demonstrator, and while Dassault and Airbus aim to fly a fighter technology demonstrator by 2026, neither programme is necessarily any further ahead than Tempest.

Some would argue that this apparent ‘early lead’ may actually condemn these programmes to being far behind Tempest when they eventually produce an in-service aircraft. Essentially, these programmes are following a more traditional model – setting the requirement early, designing the solution, and then refining and testing it.

And if the capabilities and characteristics of the core element are set in stone, then it follows that the design of the other elements will be less flexible and less adaptable.

By the time most aircraft programmes become public knowledge, a configuration has been chosen, and concept artwork usually bears a close resemblance to the eventual production aircraft. Michael Christie, however, has already cautioned that the fighter that emerges from the FCAS programme “may not look like the concept aircraft unveiled in 2018.”

Carrier implications

Adapting the core manned Tempest fighter for carrier operations would be a massive task, and one that would impose tight constraints on the design. The aircraft would need to be able to withstand the stresses and fatigue loads imposed by arrested carrier landings and catapult launches, which would increase structural weight, although overall mass would still need to be kept relatively low.

Quite apart from weight limits, the size of aircraft carrier deck elevators would restrict the aircraft’s overall length (and wingspan). Other design requirements would include a rugged, long-stroke carrier landing gear with associated additional internal volume and a suitable arrester hook, that would need to be fully retractable to preserve LO characteristics. Carrier operations would also demand enhanced corrosion protection, and potentially different LO treatments/ coatings.

Take-off performance and lowspeed handling and control authority would need to be adequate for catapult launch. The aircraft would need to be able to flya standard carrier approach, with the pilot getting a good view ‘over the nose’.

Although BAE produced full-scale models of a notional Tempest design, and displayed them at airshows at Farnborough, Fairford, Cosford and Duxford, and despite multiple computer-generated renderings and animations showing the same basic twin-finned, twin-engined tailless Delta design, the FCAS core element could look very different indeed.

“The future of air operations will be about rapid and large-scale information exchange”

– Iain Bancroft, director of major air programmes, Leonardo

When AIR International spoke with Michael Christie in March 2021, he said “we’re still looking at multiple options for the configuration of the core, manned, or optionally manned platform. We’re looking at the balance between the various components and at how best to distribute capability across the overall system.

We will model various different sizes and shapes and the different capabilities and roles that each of the components carry out, trying to find the balance between the most effective and the most affordable.

So we will be keeping our options open for a while yet.”

What this means is that other elements of the ‘system of systems’ can be adapted to compensate for features that might be missing from the core platform, or vice versa. For example, if it is found to be more efficient and cheaper to leave penetrating reconnaissance to an adjunct, then that can be done.

The NGAD and SCAF teams, working in a more traditional way, will very soon have to determine exactly what level of LO will be required –a decision that will result in the design being frozen. Team Tempest can continue to mull that over, and to take account of changes to the threat, and of the performance and characteristics of different adjuncts and effectors.

Christie was unwilling to say how many configurations were being examined.

“We’re looking at many configurations. But I don’t really want to give a number because I don’t think it means that much. We have the ability to assess many more configurations than before,” he said.

“If I look back to the days when I was an aerodynamicist on Typhoon, we looked at a range of different configurations, the P110, P113, P120, etc. We had to go through a whole series of wind tunnel tests and gradually mature the product. I could never have depended on computational fluid dynamics in those days to do that.

“I can do that synthetically now an awful lot more quickly than I was able to do it back in the 1980s. We can rattle through these configurations at a great pace. We can do things in a matter of days that would literally have taken months and years. In some of the work we’ve done, we’ve been able to run 60 configurations through a high-performance computer, again in a matter of days.

A digital thread runs right through the Tempest programme, from concepting, through to design, manufacturing, sustainment and operation

Ray Troll

“But I don’t necessarily want everybody continually looking at lots of configurations. We need to make a clear decision.”

One of the concepts that has been looked at is to treat the core fighter as a ‘minimum viable platform’, adding software and plug-and-play equipment modules to flex its role, rather than treating the aircraft as a multi-role platform in the traditional sense. The same airframe shape would perform different roles, according to what equipment was fitted, but the different aircraft would fundamentally share the same platform.

New design techniques

The Boeing/Saab T-7A programme demonstrated that by using advanced digital design and cutting edge manufacturing it was possible to produce a brand new, clean sheet of paper airframe more cheaply than simply buying an off-the-shelf trainer. Dr Will Roper, the Pentagon’s former Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics, exploited this capability when he outlined his new ‘Century Series’ concept for building future fighter aircraft.

Roper urged the development of a series of shorter-lived aircraft programmes that would share some common components and subassemblies. Roper’s vision saw new designs being rolled out on a predictable cycle, replacing older models in production – much like new versions of the iPhone. Roper wanted to see a rapid iteration of new designs, rewarding the “volume of design”, not production numbers.

The core Tempest aircraft will be augmented by a host of adjuncts and effectors, including UAVs of various shapes and sizes, among them ‘loyal wingmen’ and attritable swarming drones

A similar approach to FCAS could theoretically see different operators procure different elements of the ‘system of systems’ – perhaps with a different core platform to suit different requirements – Sweden, for example, might want a lightweight fighter optimised for operation from austere road strips, while another operator might prefer a narrowly focused BVR system.

But while Christie admits that he “bought into some of the thinking of the century series,” he cautions against trying to design too many different platform types, “because there’s a non-recurring cost to doing that.”

This view of the Tempest configuration shows to advantage some of the LO characteristics that will feature on whatever configuration is eventually chosen

The cynical observer might suspect that BAE Systems is unlikely to embrace small production runs of aircraft, having spent the last three decades becoming more and more adept at exploiting today’s combat aircraft business model, which rewards production longevity and numbers over dynamic design. The more aircraft a manufacturer builds, the longer that company will be able to earn money from sustainment and support revenues.

Fixed jigs will be rare in BAE Systems’ ‘factory of the future’, but advanced robotics will be clearly in evidence

Carrier capability

There have been numerous suggestions that the Tempest programme could or should produce a carrier-capable version (see Carrier implications, page 24).

When Labour peer Lord West of Spithead (the former First Sea Lord) asked about this in February 2019, Earl Howe, the Minister of State at the Ministry of Defence, said that any new combat air system would “need to be interoperable with the Carrier Enabled Power Projection (CEPP) programme.”

He added that carrier basing would be considered “for any unmanned force multipliers which may form part of the future combat air system,” while seeming to imply that there would be no requirement for a manned combat aircraft on the carrier beyond the F-35.

There is a significant ‘carrier lobby’ in the UK, and some still press for a carrier-based version of the core manned fighter.

AIR International asked Michael Christie how dismayed he would be if someone told him that there was now a requirement to operate Tempest from a carrier.

“I’d be surprised, but I might not be dismayed. It will definitely be a challenge to do everything that we’re trying to do and also make it carrier suitable.

If that’s a decision that is going to be made then it has to be made early, because it will have a profound effect on the configuration.

Carrier capability would have to be built into the requirements. I don’t think it’s likely to be a requirement given that the UK already has a carrier capability.”

With so much still to be decided it will be some time before anyone sees anything approaching a final Tempest aircraft design, even though Team Tempest is aiming to achieve an IOC (Initial Operational Capability) in 2035, with FOC (Full Operational Capability) in 2040.

To get hung up on the configuration would be to fundamentally misunderstand what the FCAS is all about.

Six major workstreams

When looking at Tempest, it is tempting to concentrate on some of the exotic technologies that the aircraft will or might incorporate. Much has been written about future ‘virtual cockpit’ technologies, haptics (technology that simulates what would be felt by a user interacting directly with physical objects) and wearable technologies, and even directs energy weapons.

But perhaps more significant than these individual technologies are the six major workstreams that make up the programme.

The first of these is concepting, which Christie describes as being “almost like the integrating workstream.”

The second workstream covers next-generation technologies, many of which cannot be talked about, but which include low observability.

The third includes both power and propulsion technologies, and the fourth covers sensing technologies, while the fifth is based around airframe technology.

The sixth workstream is built around enabling technologies, including manufacturing, model-based systems engineering, and the digital enterprise.

The key to success for the next generation of combat aircraft will be what is now called ‘dominance in the information space’. It is all about finding, disseminating and exploiting information, and this will place a huge emphasis on new technologies, including artificial intelligence and autonomy.

To succeed in a rapidly changing threat environment, the system will have to be rapidly reconfigurable and upgradeable.

This will require open architectures in the FCAS but also in the design, development and manufacturing sphere, as well as very agile project management. Everything about Tempest will be quite different to the way that BAE Systems and its partners have managed and executed combat aircraft programmes in the past.

Those who value aesthetics in aircraft design may be reassured by the reminder that this, now very familiar twin-finned, pelican-nosed configuration – may not be the final Tempest design

“The sooner you lock down the design, the sooner it’s obsolete!” – Andrew Kennedy, strategic campaigns director, BAE Systems Air BAE’s ‘factory of the future’ is emblematic of the new approach. A digital thread runs through the entire process, from concept work, through to the design process and into manufacturing.

This Tempest configuration appears futuristic and ‘stealthy’, and that’s probably why it was chosen to form the basis of full-scale models and press imagery. It looks as you’d expect a midcentury sixth-generation fighter to look – twinfinned, tailless, delta winged. However, the real thing could turn out very differently

The new factory will move away from fixed jigs as far as is possible and will make unparalleled use of robotics and additive manufacturing (3D printing). Furthermore, it promises to reduce timescales, leveraging higher yields and a higher ‘right first time’ rate.

The future of air operations will entail a ‘system of systems’, with multiple assets exchanging information constantly within the air domain, and across land, sea, space and cyberspace

Programmatics

Getting to grips with the work of Team Tempest and the FCAS project means understanding that there are now effectively two related programmes running in parallel. One is a British national combat air acquisition process, while the other is a trilateral international technology programme.

The UK effort will move into its concept and assessment phase this summer, using funding allocated in the 2021 Defence Command Paper, ‘Defence in a Competitive Age’.

The national and international programmes have run in parallel, but the intent is for both to coincide at some point later in the year, moving to a joint statement of work and then joining together in a single organisational structure later in the programme.

This has been laid out in the Trilateral MoU signed by the Swedish, Italian and UK governments at the end of last year.

After the concept and assessment phase, the next big milestone will be the alternate systems review, which is when the system will be defined, and when the formal requirement will start to firm up. There will be a much clearer idea of what the system will be, and what the elements of the system are.

The alternate systems review for the overall ‘system of systems’ is probably 18 months away from starting, while the core platform review is probably two years away.

The whole process will be far less sequential than traditional programmes, with much more work being conducted in parallel. In a traditional programme the customer issues a requirement, to which industry then responds. But for Tempest, there is a more iterative process between customer and industry, with dynamic operational analysis, and with system development proceeding simultaneously.

Partnership

“One of the core tenets of the Future Combat Air System programme is that it is definitely international by design,” Michael Christie says.

“On day two, as soon as we had unveiled the concept model, we started talking to our partners in Sweden and Italy. We’ve got a group of nations who have come together and who want to, and know how to, collaborate.”

Christie explained further: “We have a very good coverage of all the capabilities that are required to bring a complex combat aircraft system into play.

We all understand how to compromise and come up with a solution that works for everybody.

That in itself is as important as some of the technical skills. In this market if you know how to come together and work effectively as a team you’ve probably got a bit of a winning formula.”

As well as the three key nations of the UK, Italy and Sweden (each of which is capable of designing and manufacturing whole aircraft, and each of which has capabilities in sensing and weapons), the UK partners are determined to make the programme accessible to new partners joining later.

“All of the partners working together at the moment are experienced in the export market, and we’re experienced in how you gain export customers in this very complex sector,” Christie insisted.

“I know from my time working on Typhoon and Hawk exports that you don’t do exports these days without having some kind of share of the work going to your export partners.

“One of the lessons learned from previous programmes is that if it’s all too tightly ‘stitched up’ up-front, it becomes very challenging later in the programme. So this is a programme that has set out to be international by design.”

Those involved are also determined to ensure that any new Tempest partner will have some level of freedom of action in terms of both operational sovereignty and freedom of modification.

Industrial construct

One of the most important tasks over the next few months will be building the necessary governmental and industrial constructs. “Rather than starting with a structure, we’re starting with an outcome in mind, and this is that we want an efficient, competitive delivery construct,” explained Michael Christie.

Team Tempest is looking at a very wide range of alternative structures, and is hoping to learn from NETMA, Panavia and Eurofighter, as well as from other consortia and similarly complex programmes.

The team wants to avoid duplication in the delivery construct, and needs to move at a very rapid pace if it is to meet the ambitious target of an IOC of 2035.

It is still too early to say what the Tempest platform will look like, what adjuncts and effectors will form the other elements of the Future Combat Air System, or even exactly how the programme will be run. What is certain, however, is that the Tempest Team will shake up FCAS development once and for all.

https://www.key.aero/article/team-tempest-takes-new-approach

None of your own words then 😆 Are you trying to pinch UKDJ’s job. I do agree with you on Tempest though.

The Russians and Chinese my be Close to parity with the West in 5th Gen but not the numbers. Both countries have majority 3/4 gen planes and only a number of 5th gen.

Not by 2024/5 when the US admits they will have more 5th gen than them. I posted the link to this story in another thread.

From a senior Airforce General, I believe who is based in the Indo- Pacific region.

Some more news on that front.

Report: New Stealth Aircraft and Capabilities in China’s Air Arms Eroding U.S. Advantages Nov. 4, 2021

https://www.airforcemag.com/report-new-stealth-aircraft-and-capabilities-in-chinas-air-arms-eroding-u-s-advantages/

I cannot believe that the u.k has involved itself in a project that doesn’t involve aVSTOL version

“Can you begin to imagine trying to sort out this mess? I have and when you start to add different requirements for different customers, the problem simply becomes even more unmanageable.”

The same issues will apply to the Tempest program in a few years down the line. Most likely with Sweden wanting different requirements out of the aircraft and other customers too.

Not the case, fortunately. Note the part in relation to carrier ops.

“If I look back to the days when I was an aerodynamicist on Typhoon, we looked at a range of different configurations, the P110, P113, P120, etc. We had to go through a whole series of wind tunnel tests and gradually mature the product. I could never have depended on computational fluid dynamics in those days to do that.

“I can do that synthetically now an awful lot more quickly than I was able to do it back in the 1980s. We can rattle through these configurations at a great pace. We can do things in a matter of days that would literally have taken months and years.

https://www.key.aero/article/team-tempest-takes-new-approach

I wonder what’s happening behind closed doors? Enjoy your breakfast Daniele!

14th April 2021

FEATURE

“In this exclusive look behind the scenes of Britain’s new Future Combat Air System, Jon Lake gets under the skin of an aircraft due to enter service in just 14 years’ time, and yet its configuration is still undecided.

Tempest will be a ‘system of systems’ with a manned (or optionally manned) fighter aircraft at its heart – the final design, however, may differ substantially from the configuration featured in BAE Systems’ marketing effort

The Tempest name refers to a planned new fighter aircraft expected to sit at the heart of what will be a ‘system of systems’, consisting of crewed and uncrewed platforms, weapons, sensors and other force elements. That ‘system of systems’ is also called Tempest, and to add to the risk of confusion, the UK industry team working on this whole Future Combat Air System (FCAS) is known as Team Tempest.

The aerospace industry has long been somewhat platform-centric, based around the development and production of a particular aircraft type. In more recent times, those aircraft types have been ‘weapons systems’, and the sensors and fire control systems they carry have become progressively more important.

Those systems are today at least as significant as the airframe and powerplant, but the aerospace industry has continued to focus on building individual platforms.

The product has always tended to be a standalone platform, albeit one equipped with important sensors, systems and weapons. By contrast, the new FCAS, rather than being a single standalone platform, will be a connected network of capabilities, hence a ‘system of systems’.

This new approach is required because air forces are facing a very complex and dangerous threat environment that is changing rapidly, and one that is proliferating around the world.

Technology (and especially threat technology) is changing so rapidly that the framework of the new FCAS needs to be extremely adaptable, responsive and upgradable.

Leonardo’s director of major air programmes, Andrew Howard, told AIR International that “the future of air operations will not be about groups of individual aircraft flying individual missions in a warfighting posture.

It will be about rapid and large-scale information exchange across a network of distributed capabilities, on an almost constant basis, within the air domain, and across all other domains, such as land, sea and space.

This ‘system of systems’ model underpins the Tempest concept and requires a completely new approach.”

Elements and categories

The core element is “likely to be a manned or optionally manned system but there will be a number of other systems or components that sit around it,” said Michael Christie, BAE Systems’ director of future combat air systems, and the company’s senior representative on Team Tempest. Christie defines these elements according to four broad categories. As well as the first, the core platform, there are what he calls adjuncts, a more generic term for the loyal wingman/remote carrier unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs) that will also be developed.

These could have a range of different capabilities, and could even fulfil different roles.

The third category refers to ‘effectors’, a term Team

Tempest prefers to ‘weapons’ because they may not deliver kinetic effects. The final category is command, control and communications.

A radical approach

The UK-led FCAS and the next-generation Tempest aircraft at its core are being developed in a radically new way, and this can make the programme difficult to understand and to follow.

Judged by conventional metrics, the programme might appear to be lagging behind rival US and Franco-German-Spanish efforts to develop new-generation combat aircraft and combat air systems, for example, but to make that assumption would be a mistake.

Although Team Tempest is looking to produce a flexible, affordable combat aircraft that reaches the market in the 2030s, the team is in no rush to get an aircraft into the air or even to lock down the design.

Development of Tempest is proceeding apace, but there are few obvious milestones or markers of progress since a key feature of the programme is that it is quite deliberately concentrating on developing and maturing the technologies and capabilities required.

Platform development will be compressed and left until the last moment, thanks to extensive and indeed unparalleled use of model-based systems engineering and design.

Quite simply, this is because, as Andrew Kennedy, head of group strategy, BAE Systems Air, observed: “The sooner you lock down the design, the sooner it’s obsolete!”

Michael Christie acknowledged that this approach means that “some people are nervous – it feels like you’re not firming things up until later, and that’s partly true, but what you also get from it is much greater maturity, much greater understanding of the system and how it works, so that you don’t spend the period taking a requirement and translating it into a product, trying to work out what the requirement really means.”

Leonardo’s Andrew Howard gave more details: “Traditionally, the capabilities we could bring to the battlespace were restricted at an early stage by the decisions made in designing a platform. An aircraft would be designed and built, and then companies like Leonardo would work to equip it with useful technology.

If you wanted a specific capability, but it wouldn’t fit on the aircraft, then straight away you’ve got a costly and time-consuming problem to solve. We, as Team Tempest, have recognised that this model is no longer fit for purpose.”

What this all means is that although the US NGAD programme already has a flying demonstrator, and while Dassault and Airbus aim to fly a fighter technology demonstrator by 2026, neither programme is necessarily any further ahead than Tempest.

Some would argue that this apparent ‘early lead’ may actually condemn these programmes to being far behind Tempest when they eventually produce an in-service aircraft.

Essentially, these programmes are following a more traditional model – setting the requirement early, designing the solution, and then refining and testing it.

And if the capabilities and characteristics of the core element are set in stone, then it follows that the design of the other elements will be less flexible and less adaptable.

By the time most aircraft programmes become public knowledge, a configuration has been chosen, and concept artwork usually bears a close resemblance to the eventual production aircraft.

Michael Christie, however, has already cautioned that the fighter that emerges from the FCAS programme “may not look like the concept aircraft unveiled in 2018.”

Carrier implications

Adapting the core manned Tempest fighter for carrier operations would be a massive task, and one that would impose tight constraints on the design. The aircraft would need to be able to withstand the stresses and fatigue loads imposed by arrested carrier landings and catapult launches, which would increase structural weight, although overall mass would still need to be kept relatively low.

Quite apart from weight limits, the size of aircraft carrier deck elevators would restrict the aircraft’s overall length (and wingspan).

Other design requirements would include a rugged, long-stroke carrier landing gear with associated additional internal volume and a suitable arrester hook, that would need to be fully retractable to preserve LO characteristics.

Carrier operations would also demand enhanced corrosion protection, and potentially different LO treatments/ coatings.

Take-off performance and lowspeed handling and control authority would need to be adequate for catapult launch. The aircraft would need to be able to fly a standard carrier approach, with the pilot getting a good view ‘over the nose’.

Although BAE produced full-scale models of a notional Tempest design, and displayed them at airshows at Farnborough, Fairford, Cosford and Duxford, and despite multiple computer-generated renderings and animations showing the same basic twin-finned, twin-engined tailless Delta design, the FCAS core element could look very different indeed.

“The future of air operations will be about rapid and large-scale information exchange”

– Iain Bancroft, director of major air programmes, Leonardo

When AIR International spoke with Michael Christie in March 2021, he said “we’re still looking at multiple options for the configuration of the core, manned, or optionally manned platform. We’re looking at the balance between the various components and at how best to distribute capability across the overall system.

We will model various different sizes and shapes and the different capabilities and roles that each of the components carry out, trying to find the balance between the most effective and the most affordable.

So we will be keeping our options open for a while yet.”

What this means is that other elements of the ‘system of systems’ can be adapted to compensate for features that might be missing from the core platform, or vice versa. For example, if it is found to be more efficient and cheaper to leave penetrating reconnaissance to an adjunct, then that can be done.

The NGAD and SCAF teams, working in a more traditional way, will very soon have to determine exactly what level of LO will be required –a decision that will result in the design being frozen.

Team Tempest can continue to mull that over, and to take account of changes to the threat, and of the performance and characteristics of different adjuncts and effectors.

Christie was unwilling to say how many configurations were being examined.

“We’re looking at many configurations. But I don’t really want to give a number because I don’t think it means that much. We have the ability to assess many more configurations than before,” he said.

“If I look back to the days when I was an aerodynamicist on Typhoon, we looked at a range of different configurations, the P110, P113, P120, etc. We had to go through a whole series of wind tunnel tests and gradually mature the product. I could never have depended on computational fluid dynamics in those days to do that.

“I can do that synthetically now an awful lot more quickly than I was able to do it back in the 1980s.

We can rattle through these configurations at a great pace. We can do things in a matter of days that would literally have taken months and years. In some of the work we’ve done, we’ve been able to run 60 configurations through a high-performance computer, again in a matter of days.

A digital thread runs right through the Tempest programme, from concepting, through to design, manufacturing, sustainment and operation

Ray Troll

“But I don’t necessarily want everybody continually looking at lots of configurations. We need to make a clear decision.”

One of the concepts that has been looked at is to treat the core fighter as a ‘minimum viable platform’, adding software and plug-and-play equipment modules to flex its role, rather than treating the aircraft as a multi-role platform in the traditional sense.

The same airframe shape would perform different roles, according to what equipment was fitted, but the different aircraft would fundamentally share the same platform.

New design techniques

The Boeing/Saab T-7A programme demonstrated that by using advanced digital design and cutting edge manufacturing it was possible to produce a brand new, clean sheet of paper airframe more cheaply than simply buying an off-the-shelf trainer.

Dr Will Roper, the Pentagon’s former Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics, exploited this capability when he outlined his new ‘Century Series’ concept for building future fighter aircraft.

Roper urged the development of a series of shorter-lived aircraft programmes that would share some common components and subassemblies.

Roper’s vision saw new designs being rolled out on a predictable cycle, replacing older models in production – much like new versions of the iPhone. Roper wanted to see a rapid iteration of new designs, rewarding the “volume of design”, not production numbers.

The core Tempest aircraft will be augmented by a host of adjuncts and effectors, including UAVs of various shapes and sizes, among them ‘loyal wingmen’ and attritable swarming drones

A similar approach to FCAS could theoretically see different operators procure different elements of the ‘system of systems’ – perhaps with a different core platform to suit different requirements – Sweden, for example, might want a lightweight fighter optimised for operation from austere road strips, while another operator might prefer a narrowly focused BVR system.

But while Christie admits that he “bought into some of the thinking of the century series,” he cautions against trying to design too many different platform types, “because there’s a non-recurring cost to doing that.”

This view of the Tempest configuration shows to advantage some of the LO characteristics that will feature on whatever configuration is eventually chosen

The cynical observer might suspect that BAE Systems is unlikely to embrace small production runs of aircraft, having spent the last three decades becoming more and more adept at exploiting today’s combat aircraft business model, which rewards production longevity and numbers over dynamic design. The more aircraft a manufacturer builds, the longer that company will be able to earn money from sustainment and support revenues.

Fixed jigs will be rare in BAE Systems’ ‘factory of the future’, but advanced robotics will be clearly in evidence

Carrier capability

There have been numerous suggestions that the Tempest programme could or should produce a carrier-capable version (see Carrier implications, page 24). When Labour peer Lord West of Spithead (the former First Sea Lord) asked about this in February 2019, Earl Howe, the Minister of State at the Ministry of Defence, said that any new combat air system would “need to be interoperable with the Carrier Enabled Power Projection (CEPP) programme.”

He added that carrier basing would be considered “for any unmanned force multipliers which may form part of the future combat air system,” while seeming to imply that there would be no requirement for a manned combat aircraft on the carrier beyond the F-35.

There is a significant ‘carrier lobby’ in the UK, and some still press for a carrier-based version of the core manned fighter. AIR International asked Michael Christie how dismayed he would be if someone told him that there was now a requirement to operate Tempest from a carrier.

“I’d be surprised, but I might not be dismayed. It will definitely be a challenge to do everything that we’re trying to do and also make it carrier suitable. If that’s a decision that is going to be made then it has to be made early, because it will have a profound effect on the configuration. Carrier capability would have to be built into the requirements. I don’t think it’s likely to be a requirement given that the UK already has a carrier capability.”

With so much still to be decided it will be some time before anyone sees anything approaching a final Tempest aircraft design, even though Team Tempest is aiming to achieve an IOC (Initial Operational Capability) in 2035, with FOC (Full Operational Capability) in 2040. To get hung up on the configuration would be to fundamentally misunderstand what the FCAS is all about.

Six major workstreams

When looking at Tempest, it is tempting to concentrate on some of the exotic technologies that the aircraft will or might incorporate. Much has been written about future ‘virtual cockpit’ technologies, haptics (technology that simulates what would be felt by a user interacting directly with physical objects) and wearable technologies, and even directs energy weapons.

But perhaps more significant than these individual technologies are the six major workstreams that make up the programme.

The first of these is concepting, which Christie describes as being “almost like the integrating workstream.”

The second workstream covers next-generation technologies, many of which cannot be talked about, but which include low observability.

The third includes both power and propulsion technologies, and the fourth covers sensing technologies, while the fifth is based around airframe technology.

The sixth workstream is built around enabling technologies, including manufacturing, model-based systems engineering, and the digital enterprise.

The key to success for the next generation of combat aircraft will be what is now called ‘dominance in the information space’. It is all about finding, disseminating and exploiting information, and this will place a huge emphasis on new technologies, including artificial intelligence and autonomy. To succeed in a rapidly changing threat environment, the system will have to be rapidly reconfigurable and upgradeable.

This will require open architectures in the FCAS but also in the design, development and manufacturing sphere, as well as very agile project management. Everything about Tempest will be quite different to the way that BAE Systems and its partners have managed and executed combat aircraft programmes in the past.

Those who value aesthetics in aircraft design may be reassured by the reminder that this, now very familiar twin-finned, pelican-nosed configuration – may not be the final Tempest design

“The sooner you lock down the design, the sooner it’s obsolete!”

– Andrew Kennedy, strategic campaigns director, BAE Systems Air

BAE’s ‘factory of the future’ is emblematic of the new approach. A digital thread runs through the entire process, from concept work, through to the design process and into manufacturing.

This Tempest configuration appears futuristic and ‘stealthy’, and that’s probably why it was chosen to form the basis of full-scale models and press imagery. It looks as you’d expect a midcentury sixth-generation fighter to look – twinfinned, tailless, delta winged. However, the real thing could turn out very differently

The new factory will move away from fixed jigs as far as is possible, and will make unparalleled use of robotics and additive manufacturing (3D printing). Furthermore, it promises to reduce timescales, leveraging higher yields and a higher ‘right first time’ rate.

The future of air operations will entail a ‘system of systems’, with multiple assets exchanging information constantly within the air domain, and across land, sea, space and cyberspace

Programmatics

Getting to grips with the work of Team Tempest and the FCAS project means understanding that there are now effectively two related programmes running in parallel. One is a British national combat air acquisition process, while the other is a trilateral international technology programme.

The UK effort will move into its concept and assessment phase this summer, using funding allocated in the 2021 Defence Command Paper, ‘Defence in a Competitive Age’.

The national and international programmes have run in parallel, but the intent is for both to coincide at some point later in the year, moving to a joint statement of work and then joining together in a single organisational structure later in the programme. This has been laid out in the Trilateral MoU signed by the Swedish, Italian and UK governments at the end of last year.

After the concept and assessment phase, the next big milestone will be the alternate systems review, which is when the system will be defined, and when the formal requirement will start to firm up. There will be a much clearer idea of what the system will be, and what the elements of the system are.

The alternate systems review for the overall ‘system of systems’ is probably 18 months away from starting, while the core platform review is probably two years away.

The whole process will be far less sequential than traditional programmes, with much more work being conducted in parallel. In a traditional programme the customer issues a requirement, to which industry then responds. But for Tempest, there is a more iterative process between customer and industry, with dynamic operational analysis, and with system development proceeding simultaneously.

Partnership

“One of the core tenets of the Future Combat Air System programme is that it is definitely international by design,” Michael Christie says.

“On day two, as soon as we had unveiled the concept model, we started talking to our partners in Sweden and Italy. We’ve got a group of nations who have come together and who want to, and know how to, collaborate.”

Christie explained further: “We have a very good coverage of all the capabilities that are required to bring a complex combat aircraft system into play. We all understand how to compromise and come up with a solution that works for everybody. That in itself is as important as some of the technical skills. In this market if you know how to come together and work effectively as a team you’ve probably got a bit of a winning formula.”

As well as the three key nations of the UK, Italy and Sweden (each of which is capable of designing and manufacturing whole aircraft, and each of which has capabilities in sensing and weapons), the UK partners are determined to make the programme accessible to new partners joining later.

“All of the partners working together at the moment are experienced in the export market, and we’re experienced in how you gain export customers in this very complex sector,” Christie insisted.

“I know from my time working on Typhoon and Hawk exports that you don’t do exports these days without having some kind of share of the work going to your export partners.

“One of the lessons learned from previous programmes is that if it’s all too tightly ‘stitched up’ up-front, it becomes very challenging later in the programme. So this is a programme that has set out to be international by design.”

Those involved are also determined to ensure that any new Tempest partner will have some level of freedom of action in terms of both operational sovereignty and freedom of modification.

Industrial construct

One of the most important tasks over the next few months will be building the necessary governmental and industrial constructs. “Rather than starting with a structure, we’re starting with an outcome in mind, and this is that we want an efficient, competitive delivery construct,” explained Michael Christie.

Team Tempest is looking at a very wide range of alternative structures, and is hoping to learn from NETMA, Panavia and Eurofighter, as well as from other consortia and similarly complex programmes.

The team wants to avoid duplication in the delivery construct, and needs to move at a very rapid pace if it is to meet the ambitious target of an IOC of 2035.

It is still too early to say what the Tempest platform will look like, what adjuncts and effectors will form the other elements of the Future Combat Air System, or even exactly how the programme will be run. What is certain, however, is that the Tempest Team will shake up FCAS development once and for all.”

I opted not to agree and can access it in full. I’ve done my best to sort out the paragraphs for you but it’s late!

https://www.key.aero/article/team-tempest-takes-new-approach

He’s here!

Would you like some popcorn, mate?

Oh go on then….!

I’m on nights here in box so got all evening to enjoy the show.

Hah! Don’t get up to no good in that box.

Oh, just a little breathing, surely!

Enjoy the read, Hopefully, Daniele will see the thread.

Interesting times ahead it would appear 😉

https://www.key.aero/article/team-tempest-takes-new-approach

Morning mate.

Thanks.

You’re welcome!

And with the USA contemplating the same landing gear (Carrier) to save on maintenance costs across platforms plus the our recent announcement for EMAL/CATOBAR within the next 3-5 year time frame, you start to wonder?

https://www.defensenews.com/breaking-news/2020/09/15/the-us-air-force-has-built-and-flown-a-mysterious-full-scale-prototype-of-its-future-fighter-jet/

Oohhh I hate working nights, it gets your hang overs out of sink.

Last night was a good one. I’m already awake.

One for Ron5 to answer I guess. What a shocking comment to make. Even I wouldn’t use language like that!

Former US Marine Corps captain Dan Grazier believed the line of critics was growing longer, as the combat jet failed to deliver on promised capabilities.

“The F-35 program right now is certainly a program in trouble,” Mr Grazier said.

“The last acting Secretary of Defence under the Trump administration, in a kind of parting shot in his final week … he essentially called the F-35 a piece of shit.”

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-09-08/f35-program-design-flaws-part-shortages-costs-opinions-divided/100431664

Good article. About 80% of it is extremely positive about the aircraft and it’s capability. Hence why Australia is buying it. 👍🇬🇧🇦🇺

Chris Miller (the acting Def Sec) recounted a story. He had challenged a former F-16 pilot who had moved to F-35s, to tell him about the F-35, saying, “It’s a piece of ….” The pilot had responded that it was an “unbelievable aircraft”.

What does the anti-Lightning press take from Miller’s story?

He essentially called the F-35 a piece of shit.

Talk about out of context. Thanks for checking your sources, Nigel.

I always do my best Jon.

I wonder what we have in store for our carriers and why the USA has built a sixth-gen fighter so quickly if the F-35 is such a glowing success?

It was designed to fill a gap between 4th and sixth Gen in order to keep the west ahead, now the USA is already flying a sixth Gen prototype.

Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II development started in 1995 and still cannot produce what it said on the box and not until 2030 at the current rate.

https://www.key.aero/article/team-tempest-takes-new-approach

I would imagine the experimental 6th Gen fighter built by the US is going to be a successor to the F-22, an Air Superiority Fighter, when the design finally matures in the years to come.

The F-35 is essentially a Ground Attack aircraft with an aerial combat capability. The very variant the RAF/RN has does not even have a cannon fitted as standard, and as far as I’m aware, isn’t gong to be purchased.

Yes, it will be the replacement for the F22 with a longer range for the Indo-Pacific region and ground attack capabilities.

Anything to do with the F-35 is hugely political. If you freeze out other huge US companies, be it Boeing for the the airframe or GE for the engine, there’s massive corporate money whose vested interest is to talk your solution down. In the US, there are regional and state political lobbies doing that too. It certainly isn’t a perfect plane or project, but what is?

It’s the best available at the moment. It’s the best option for years to come. Will there be something technically better coming off the production line in ten years? Probably. But remember this:

JSF competition – 1998

LM’s X-35A, B and C prototypes first flying in 2006

First LRIP orders in 2007

Full rate production 2021 – delayed due to Covid and politics.

What makes you think they’ll do better with 6th gen replacement?

USN F/A-XX 6th gen program – 2008

USAF 6th gen program announced 2010

First 6th gen prototype flies – 2020

So far the program is going slower than F-35. And it may start out only replacing the F-22 not the F-35.

Use the technological advantages we have today and learn from the F-35’s mistakes.

“The importance, Roper said, is that just a year after the service completed an analysis of alternatives, the Air Force has proven it can use cutting-edge advanced manufacturing techniques to build and test a virtual version of its next fighter — and then move to constructing a full-scale prototype and flying it with mission systems onboard.”

Sounds similar to the Team Tempests approach.

https://www.defensenews.com/breaking-news/2020/09/15/the-us-air-force-has-built-and-flown-a-mysterious-full-scale-prototype-of-its-future-fighter-jet/

Technology has certainly come on a very long way. But we are kidding ourselves if we think that developing a 6th gen platform or systems that is significantly more capable than a F35 or F22 is suddenly going to be quick and affordable. I want Tempest to succeed as much as the next guy. And they really do need a new way of thinking to make these projects a success. But it’s 15-20 years away. And navigating the politics will be just as important as perfecting the technology to turn these projects into reality. As well convincing the voting public that billions of tax payers cash is worth spending on a new MOD toy, instead of hospitals and adult social care. And industry really needs to sell it’s case that it will be money well spent. The way F35 will be developed over the years. F35 will be the 6th gen or 5th gen + option for many nations as we move into the 2030’s and beyond. If Tempest makes it to a technology demonstrator, then i think we will all feel a little more confident we can pull this off. 🇬🇧

I certainly have my reservations on the F35 however the US is building a 6th Gen fighter so quickly for the following reasons.

1) the US needs a replacement Air Superiority fighter to replace the near disastrous state of the F22 ie capable when it flies but hardly ever does, is getting long in the tooth, needs. Outlying updating, costly to maintain and running low on numbers. It’s not a strike fighter like the F-35.

2) that didn’t matter too much while enemies didn’t have 5th gen air superiority fighters (or 5th gen aircraft generally). Now they do and increasingly capable, so the US has to take action to stay competitive let alone move ahead again. However there is no establish plan for these new designs to replace F-35s at this stage they are looking to replace Super Hornets and F-16s as things stand though admittedly like the original Hornet a true strike version could potentially come about eventually from a new design.

3) it’s already flying (or is it simply a much upgraded aircraft sporting some 6th gen tech we don’t know for sure) in prototype demonstrator form because of the very synthetic computational design processes that you previously refer to that allows a prototype to exist in digital form, produced to a high degree in 3D printing tested and modified in a fraction of the time taken even 10 to 15 years ago. So despite the criticisms being made about simultaneous design and build in the f35 program being problematical (I agree) it can now be done (just as Space X has led the way and other rocket producers are building upon) very successfully and a production ready design created many years quicker than during the F-35s long drawn out gestation.

Out of interest there is a pic from Northrop of all its stealth aircraft/drones in a hanger which shows the front of a mystery aircraft that many are claiming might be their offering for a 6th Gen fighter.

This sounds exactly like what we hope to achieve with the Tempest programme. I wonder if we are sharing ideas and technology?

I found the comment on landing gear interesting. As mentioned in the article I posted on Tempest, there appears to be a design for a carrier-based variant of Tempest on the drawing board which suggests the USA are contemplating doing the same thing.

The commonality of parts between platforms seems to be the way forward and the USMC have asked for their own version of a sixth-gen aircraft in the past.

Building in landing gear which clearly has to be stronger for carrier operations would make sense across the board in this case keeping parts and maintenance costs low.

“I don’t think it’s smart thinking to build one and only one aircraft that has to be dominant for all missions in all cases all the time,” he said. “Digital engineering allows us to build different kinds of aeroplanes, and if we’re really smart … we ensure smart commonality across the fleet — common support equipment, common cockpit configurations, common interfaces, common architecture, even common components like a landing gear — that simplify the sustainment and maintenance in the field.”

As for future software development. Lessons learned from F-35 programme?

UK reveals Pyramid programme to rapidly reconfigure software across multiple aircraft types

https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/uk-reveals-pyramid-programme-to-rapidly-reconfigure-software-across-multiple-aircraft-types

What drivel, the F-22 flies every day of the week.

So it won’t really be until end of 2023/ 2024 that we’ll actually have enough airframes to put 24 on a carrier and even then we’ll still be waiting to integrate key weapons…..

Happy days! All l want for xmas is a MOD order for the next batch of F35 and three of four more P8.s

And some extra CAMM and AShMs…nicely wrapped in some shiny new canisters… please. Lol 😁 🤩

QD, you need to ping Santa now to avoid delays and disappointment!

3 or 4 more P-8’s?

I think the RAF is going to be more desperate to get an adequate number of E-7’s instead.

oh I forgot my stocking filler – another 16 Protector UAV please -all in the one stocking with spares and crews in the other one

Thx Santa BJ (yes I have been well behaved).

I’ll leave the xmas RN and Army wish list to others on this site. Place your wish list asap given current global supply chain disruptions.

Happy Friday and Guy Fawkes to all!

Don’t ever Google ‘Santa BJ’!!!!

oops!

Father Christmas has run out of spare parts so you will have to make do with this for now 😂

https://www.janes.com/defence-news/air-platforms/latest/uk-receives-new-reaper-uav-to-support-transition-to-protector

Given that a Sqn = 12 aircraft we should be looking to get:

48 F35Bs (2 x RN & 2 x RAF Sqns)

24 F35As (2 x RAF Sqns) – replaces Tornado in the deep strike role

4 F35s for Test & Evaluation Sqn

12 F35s for OCU Sqn

18 F35Bs for through life replacement

6 F35As for through life replacement.

114 aircraft in total not the 138 originally ordered but 6 front line Sqns. Can it be done?

I think the RAF have a hankering for Generation 6 Rob.

Once deliveries of Tempest are underway they will probably happily turn the F35B over the Navy.

I would work out an acceptable F35B order as follows.

4x 12 aircraft operational squadrons.

1x 8 aircraft OCU

1 x 4 OTU

10 x in use reserves

30 x maintenance/sustained fleet reserves

= 100 total….

.

Good points. To be honest I’d be happy with that IF

Tempest actually happens in an acceptable time frame.

They keep the Typhoon F1s in service to free up more FGR4s for strike rather than AD as a stop gap.

I reckon we won’t get 138, 114 or even 100 F35s, more like 60 to 80.

I’m sure you are right Rob, we need 4 squadrons of B’s to properly support Carrier Strike and make it sustainable.

The actual costs of the F35, although falling, don’t come in anywhere near projected unit prices.

I think the MOD will be well within their rights to scale back the order so long as they maintain the same level of expenditure.

I don’t like the idea of spending more on this platform than we need to. Don’t get me wrong, I think the F35 is great, and its benefited us industrially, but we need it in numbers, finished and now. By the time everything is sorted out and a solid quantity are available to us we will be well into the Tempest programme.

I just don’t see the point of buying a reasonably stealthy, yet severely performance limited aircraft in vast numbers when Tempest will be coming on line that will wipe the floor with it. If Russia ever manages to mass produce its checkmate or SU-35 the F-35 will have real competition and from the increasing interest of overseas buyers towards those aircraft this may be the case. Add in improving radar technologies and it doesn’t look quite so secure a proposition.

I think the F-35B is good on account of its VTOL, Stealth and ability to operate from austere sites, I think that is a winning combination – that will always be a sneaky card up the sleeve.

We often hear the refrain, the F-35 feels like air superiority – but it would do compared to 4.5th gen aircraft. Put it up against similarly stealthy systems with equivalent data fusion, loyal wingman drones and far superior performance and it won’t feel like air-superiority much longer.

I tend to agree with you. The F-35 has the temporary advantage of stealth but otherwise is not really any kind of fearsome combat aircraft in terms of performance.

The A would be the right aircraft for now for the RAF’s interdiction/strike role, filling the big capability gap left by the premature retirement of the Tornado wing. Interdiction and air defence are the key strategic air roles, far more critical in any conflict than manning one Harrier carrier and getting As into the RAF should really be the top priority.

I would not buy many more Bs. Looking at its capabilities compared to the A, it has

18% less weapons payload

20% lower max takeoff weight

25% less range

25% less combat radius

27% less internal fuel capacity

Yet is a third more expensive than the A (£80m compared to under £60m, rising to £100m and £80m respectively once we add the Block 1V upgrade.

It is basically a short-range tactical/close support aircraft, which is handicapped in payload and performance by having to cart around its heavy lift fan. OK for the Harrier carrier and good for army close support.

But the F-35 still has a load of technical problems to sort out and will not be fully operational until 2029, the new forecast date for the Block 1V upgrade. And now the USAF is working on a more powerful and efficient engine replacement, which will bump up the cost still further.

The jury is still out on whether it is a pup or might eventually come good.

The poster who likened it to Ajax is not that far off really, it underperforms, has umpty technical issues to sort out and is miles over budget. I would personally cut our losses for now and draw the line at 60 Bs, 3 squadrons of 10 front line aircraft, one for the RN, one for close air support and one for surge capacity.

Unit price be damned. The F-35 is free! Okay not free to use, but the first 150 or so are free to buy.

It has been consistently claimed and never denied that 12 to 15% by value of the plane is made in Britain. Like you say, good for industry.

The US says it wants to buy almost 2,500. Even ignoring all the Intenational orders, 12% of 2,500 is 300. We get 300 F-35s worth of money coming in. Roughly 50% of that trickles back to the Treasury through various taxes: Corporation, Income, NI, VAT etc. The Treasury will get enough money to buy 150 F-35 through US subsidy alone.

What can stop that from happening? If enough people talk the plane down, the US might decide to buy fewer planes. If the UK buys fewer planes, we are more than talking it down; we are walking the talk. We are shooting ourselves in the foot.

We should immediately talk about buying “around” 138 again, even say it might be more than we originally planned. Good F-35 headlines help the UK.

And you know what? I think we should mean it. If we have to, don’t convert the first planes to Block 4, ditch them or turn them into trainers and buy more! If we can keep the US on track, it will costs us less in the long run.

It’s not a good plane, it’s a great plane, and will remain so for at least the next twenty years. If we are lucky enough that Tempest produces a cheaper to run and better aircraft, we can flog the old F-35s to America, like we did the Harriers, although please let’s actually have the new planes first this time.

It’s always the case that future non-existant stuff sounds better than what we can have today. But you can’t shoot down a real enemy with a virtual design.

A YANK here,One of the most on point articles ever written.

“ It has been consistently claimed and never denied that 12 to 15% by value of the plane is made in Britain.”

That figure has been torn apart many times…

The MoD word it carefully….its ‘up to 15% made by British owned companies…’. RR make the lift fan for the B in….Indianapolis, Survitec make survival gear….in the US, Martin Baker make the seats…in the US…and on and on and on.

The maximum made in the UK content is around 5-7%.

That’s a pity. We only get the first 80 planes free. Hey ho. 48 down, 32 more to order.

Not free…just recovering the development costs that were pumped in !

What concerns me is when one talks of procurement costs and the article I read explained the difficulty in like for like comparisons admittedly the F-35 didn’t come in at massively more than Typhoon. So what may we ask will Tempest come in at especially if fewer aircraft are actually built in a competitive environment.

And when do you think Tempest will be available at strength? 20 years?? F35 is fine. The current schedule makes sense against Block 4.

“…when Tempest will be coming on line that will wipe the floor with it”

” Put it up against similarly stealthy systems with equivalent data fusion, loyal wingman drones and far superior performance”

Lots of assumptions in one post on an aircraft and capabilities that are essentially vaporware at this point and for the foreseeable future. You’re also assuming that the F35 will be standing still while these other aircraft catch up to it. The f35 undeniably has it’s share of flaws, all cutting edge capabilities do. It’s interesting that even with all these well publicized flaws and cost growth, it seems to win the competition almost every time it’s demonstrated to countries looking to buy a new fighter aircraft.

Difficult to say for sure. The Indians did war games between Thai ( I think ) Gripens and their own Russian fighters ( far superior on paper) and found that in dog fighting they thrashed the lower power Gripens but at medium + range the results were reversed due to superior sensors and missiles.

I reckon 80 is towards the max unless Tempest gets into trouble.

I suspect the talk of tempest is 99% a smoke screen to avoid stories of cuts. I doubt the RAF want the tempest over the f35, as it would be a paper plane that might never get built over one that can do stuff today. I’m sure the RAF will love tempest when and if it happens, but that is still a long way off.

F-35 is a completely different aircraft compared to Tempest. One is a Strike aircraft, the other is an Air Superiority Fighter. It’s like comparing apples and oranges.

Tempest doesn’t exist, you can’t compare to to anything. The idea it will be a air superiority fighter is very unlikely. The typhoon was meant to be one but was changed and changed over the years, because dog fighters were just not required for most realistic wars.

I’m not sure the Typhoon bit is quite right Steve.

It was indeed conceived by the RAF as an air superiority fighter, primarily to engage hostiles beyond visual range, but with the agility to survive a close-in encounter within visual range.

The need for some ground attack capability became more urgent due to the perceived vulnerability of the Tornado in the low attack role, hence the switch to the FGR4.

Typhoon remains an air superiority fighter but with a secondary ground attack capability. I hope that Tempest follows that template and doesn’t end up trying to be all things to al men, the design differences between ‘fighters’ and ‘bombers’ are considerable, and a carrier-based version has a third set of parameters all to itself.

The F-35 programme has underlined the impracticallity of trying to get one airframe to fulfill 3 very different roles.

To me the future isn’t an agile fighter jet, its a big missile truck that has a large number of beyond visual range missiles, for both air and ground attack. If the beyond visual range missiles work as advertised, then the idea of an agile fighter is just not needed anymore.

Thats not the case at all.

The Typhoon was developed under a staff target to specifically replace the Jaguar and Phantom. It was supposed to have A2G capability from the off. It was never supposed to replace Tornado F3. However the post Cold War drawdown meant that the UK had lots of strike aircraft (Tornado GR, Harrier and Jaguar with life left in them). The Germans were looking for cost reductions and replacing the Phantoms (for UK and Germany) and F-104 (for Italy) became the priority. As a result the A2G capability was cut back to save funds, but the intention was always to revisit it. Time moves on though so with further drawdowns the Typhoon ended up replacing F3 and GR4.

There is still the nuclear weapon delivery consideration.

At some point it might even be cheaper to rebuild WE177s.

Wonder how many of the 48 will end up being Like Typhoon T1…and unsuitable for upgrade / long term retention ….stop thinking like that Pete….be positive.

Hi Pete,

I believe they can be upgraded and with half the airframe hours still left. We need something and in numbers for Air Intercept duties until the arrival of Tempest.

The F35 can only fly supersonic in short bursts of 50 seconds without risking damage to their stealth coating and sensors positioned near the tail.

The upgrade developed by Airbus includes modifications that integrate Tranche 2 and Tranche 3 equipment on the aircraft, not least a Computer Symbol Generator, Digital Video and Voice Recorder, Laser Designator POD and Maintenance Data Panel.

https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2019-02-airbus-delivers-first-upgraded-tranche-1-eurofighter-to-spanish-air

Agree they should extend if they can and good to see some basic upgrades going through. My rather poorly communicated thoughts were meant to be sarcastic around the lack of political will to retain, retire early on the excuse of them being not viable to retain and then allow the front line force of F35 to remain small and save a few quid in operating costs

I see where you#re coming from! 😀