Ferguson Marine is trying to re-establish itself as a functioning industrial yard rather than a political storyline. New CEO Graeme Thomson presents the current phase as a chance to rebuild capability, reset expectations and anchor the yard inside the wider supply chain.

The focus is on where the yard can credibly compete, what technical steps must come first, and how it can move from episodic, stop-start work to a stable production rhythm that contributes consistently to national output.

That context shapes how he talks about defence involvement. The experience gained from supporting Type 26 has already altered internal assumptions about what is achievable. “BAE Systems have made a play on this industry and have come to us,†he said. “We secured that work. We are in discussions about potentially future work as well from them.â€

He leaned heavily on his own project background when describing what the Type 26 relationship had forced the yard to tighten. “Having come through from a prime, from the MOD, the Type 26 and the flowdown of what is required, that has enabled us to sharpen a pencil on both the quality of our delivery, particularly in the project management side,†he said. “Having worked for BAE Systems for many years, I know the need for good robust project management.â€

The exposure to prime contractor expectations has been significant. “What they have shared through their contract with us is things I would recognise from a previous life,†he said. “Doing that work with BAE Systems has allowed us to implement tighter project management and controlled reporting. You see the effect on the product and the way we manage it through delivery.â€

This is not framed as a one-off uplift, but as part of a longer positioning strategy. “It gives BAE Systems more confidence in us, hopefully secures more work, and at the same time we will look to secure potential work from Babcock as well,†he said. “We are keen and willing to get positioned so we can support the defence sector as a tier two supplier.â€

Moving away from single vessel cycles

Thomson was clear about the structural problem he inherited. The yard cannot function if it remains dependent on one ferry at a time. “We cannot be solely a ferry builder and be in this sort of survival mode every two or three years,†he said. “We need a portfolio. One, to spread our overhead. Two, to manage our skills effectively.â€

The portfolio he describes is deliberately mixed. “Supporting the defence work, significant commercial work, and smaller vessels as well,†he said. It is intended to smooth the production rhythm and protect the yard from the gaps that have caused operational stagnation in the past.

He points to wider industry conditions that make this moment unusual. “In my 40 years, mainly in the defence industry, it is the busiest I have ever seen it,†he said. The implication is clear: if Ferguson Marine is going to reposition itself within the broader market, this is the moment to do it.

The industrial basis for competitiveness

While the broader strategy revolves around diversification, the internal reality is that competitiveness depends on upgrading processes, tools and data systems. Thomson was explicit. “We are not where we need to be in terms of a modern shipyard,†he said. “My perception is there are areas that have not been invested in: technology, equipment, structured training.â€

He outlined several early modernisation steps, many of which are already funded. “A modern advanced manufacturing panel line, a plate-cut machine, an ERP system as a good solid data backbone for the business,†he said. “These are near-term investments we will be making with support from the Scottish Government.â€

He sees these as prerequisites for stable competitiveness. “All of that moves into being a more competitive, higher-quality, innovative yard,†he said. “Commercially competitive at least in the UK.â€

Thomson framed competitiveness relative to what the National Shipbuilding Office laid out in its recent strategy. “One hundred of the 150 ships over the next 30 years are non-military,†he said. His aim is for Ferguson Marine to be the natural supplier for part of that category. “A good, efficient, yard in the West of Scotland that delivers vessels up to about 100 metres,†he said.

Preparing for the next phase of digitalisation

A recurring theme was the idea that the yard’s late start in modernisation may produce an advantage. Thomson wants the yard to leapfrog older digital frameworks adopted by competitors a decade ago. “You can only go as far as technology lets you go at that point in time,†he said. “You invest, you get what you get, then you are just doing iPhone updates of that.â€

He sees the current moment as a chance to rethink the concept. “We have a great opportunity as we go through modernisation to do the next consideration of what is a digital shipyard,†he said.

He has already sought academic input. “I asked the university what AI really means for a shipyard,†he said. “How do you take that sound bite and turn it into a tactical, actionable, successful implementation?â€

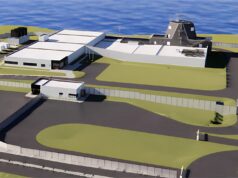

His expectation is that the yard, if it secures stable work, will look markedly different within five years. “You will see modern advanced manufacturing, people being efficient, a clean working environment,†he said. “And you will see us using technology not seen in our shipyards just now.â€

A role within the wider UK shipbuilding ecosystem

Thomson’s view of the yard’s eventual place in the national landscape is straightforward. It is not intended to be a prime contractor, nor a niche craft yard. Instead, he argues for a mid-weight role that complements rather than competes with the major integrators.

“You have six or seven major yards across the UK,†he said. Babcock, BAE Systems, Cammell Laird, Navantia UK, and A&P Group. “We want Ferguson’s in there as part of that infrastructure.â€

He added that credibility must be rebuilt through delivery. “We want to be a trusted part of the ecosystem,†he said. “Able to stand on its own but also come and play as part of a team where work needs to be distributed.â€

His closing summary captured the transitional phase he believes the yard is in. “We have had a bad game,†he said. “Some of the players have changed out. Other ones have come in. We have changed the management. We are making some investment in our process. We want the opportunity to demonstrate what we can do.â€

The opening part of the series can be accessed by clicking the image underneath this article. The concluding piece, which examines training, leadership depth and the culture Thomson is trying to build, will follow tomorrow.

I love how he is talking about the national ship building strategy like it’s a thing.

It’s not a thing, it never was a thing. It was done by a government which no longer exists and even when it did that same government completely ignored any of its findings and was quite content to go out to foreign yards to save a few quid every time hence Navnatia building FSS.

The vast majority of the ships that the report identified are procured by local and regional governments and the UK government has no control over them and never even attempted to involve them in its “strategyâ€

Ferguson should focus on building blocks for BAE, there is a proven market there and with the Norway deal and hopefully more to come there will be plenty to keep them going for decades.

Building small ferries is probably a niche they can carve out because no one wants to sail a small ferry from China or Turkey to the UK but it’s hardly a major industry worth public investment or the cost of nationalisation of Ferguson.

It’s more like yacht building which we do alot of anyway

Notwithstanding your pessimism I think that this is a better news story than you think. The CEO sounds like a man with his feet firmly planted and who is not going to go down the route we have seen so often in the past, when an ailing company acts like a bird in the nest with its mouth open waiting to be fed by a benign government. If he can get his strategy right, starting with shifting the dead wood out of the management chain, and then getting a reasonable order book then he could be on the right road. When Bae sign the Norwegian order, which should be soon then they will need a greater flow of steel work to keep to the delivery schedule. Ferguson have already delivered some modules so should be well placed to continue that work. If they can then diversify as well into the up to 100m space then you will have a viable shipyard.

As the man said this could be a good time to be rebuilding a company in the shipyard business.

Assuming they have been good at QA.

That also presupposes that BAES don’t have plans for more kit in the old sheds as they will now have plenty of space to fabricate and consolidate blocks.

“ Building small ferries is probably a niche they can carve out because no one wants to sail a small ferry from China or Turkey to the UK but it’s hardly a major industry worth public investment or the cost of nationalisation of Ferguson.â€

Small vessels go deck cargo or are out on a lifter ship / barge.

Yes but deck lifters are expensive and small ferries are typically too big to be shipped deck cargo. Also small ferries with small costs are typically not worth the time of large international tenders.

Cammel laird is already on this market in the UK.

Errrr well the small ferries are not bought one at a time.

The lifters could take 2-3 of them.

However you slice and dice it Fergusons are not going to be competitive building ferries without massive subsidy. There are some things we have to let go of and focus on the bits were UKPLC can add value.

He sounds like he has his head in reality.

In the short to medium turn there’s plenty of work supporting BAE on the Clyde.

That should basically underwrite the yard and pay for new systems and a panel line

Then they can start bidding for ferries, and unarmed fisheries protection vessels

Though personally I’d put my money on Cammels simply because Merseyside is cheaper