At an event today at Officine Farneto in Rome, Leonardo presented what it describes as a new approach to European air and missile defence, built around real time data fusion and AI assisted decision making.

Chief executive Roberto Cingolani delivered a dense technical briefing that outlined both the scale of the threat picture he sees emerging and the industrial reorganisation he argues is required to match it.

From the outset, Cingolani stressed that Michelangelo is intended to be built with military operators rather than handed to them. “The project that we are presenting today will become an integrated project team,” he said. “It will be a mixed team of all of the Leonardo armed forces projects. They’re the ones who will be designing this new Michelangelo architecture based on the needs of our defence forces.”

He contrasted that with what he views as a persistent cultural problem in European technology development. “The main mistake we can make is to think we make this kind of technology, a wonderful mobile phone which becomes trendy. That is consumer technology. This technology that Europe’s security depends on can only be designed with armed forces.”

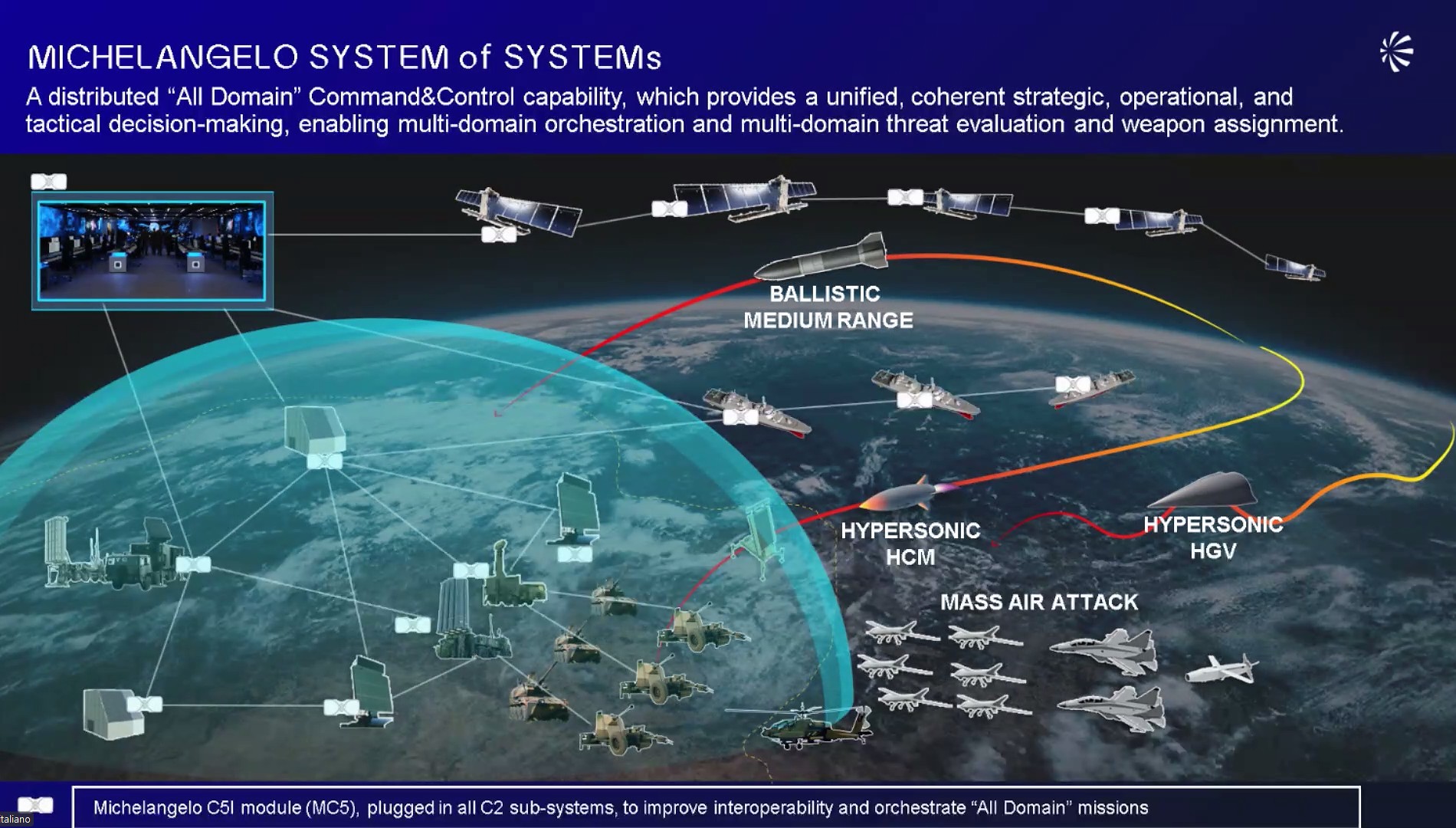

Most of his briefing focused on what he called a genuine multi-domain operating concept. Cingolani pointed out that older doctrines kept land, air and maritime assets largely separate. “According to the older technologies and doctrines, these assets would not communicate with one another. Each had its own task on land, in air, at sea.” The goal behind Michelangelo, he said, is to create the connective layer those doctrines lacked. “Multi domain means bringing together industrial policy, allowing us to have a portfolio of platforms which float, which are on land, which fly or which are in space.”

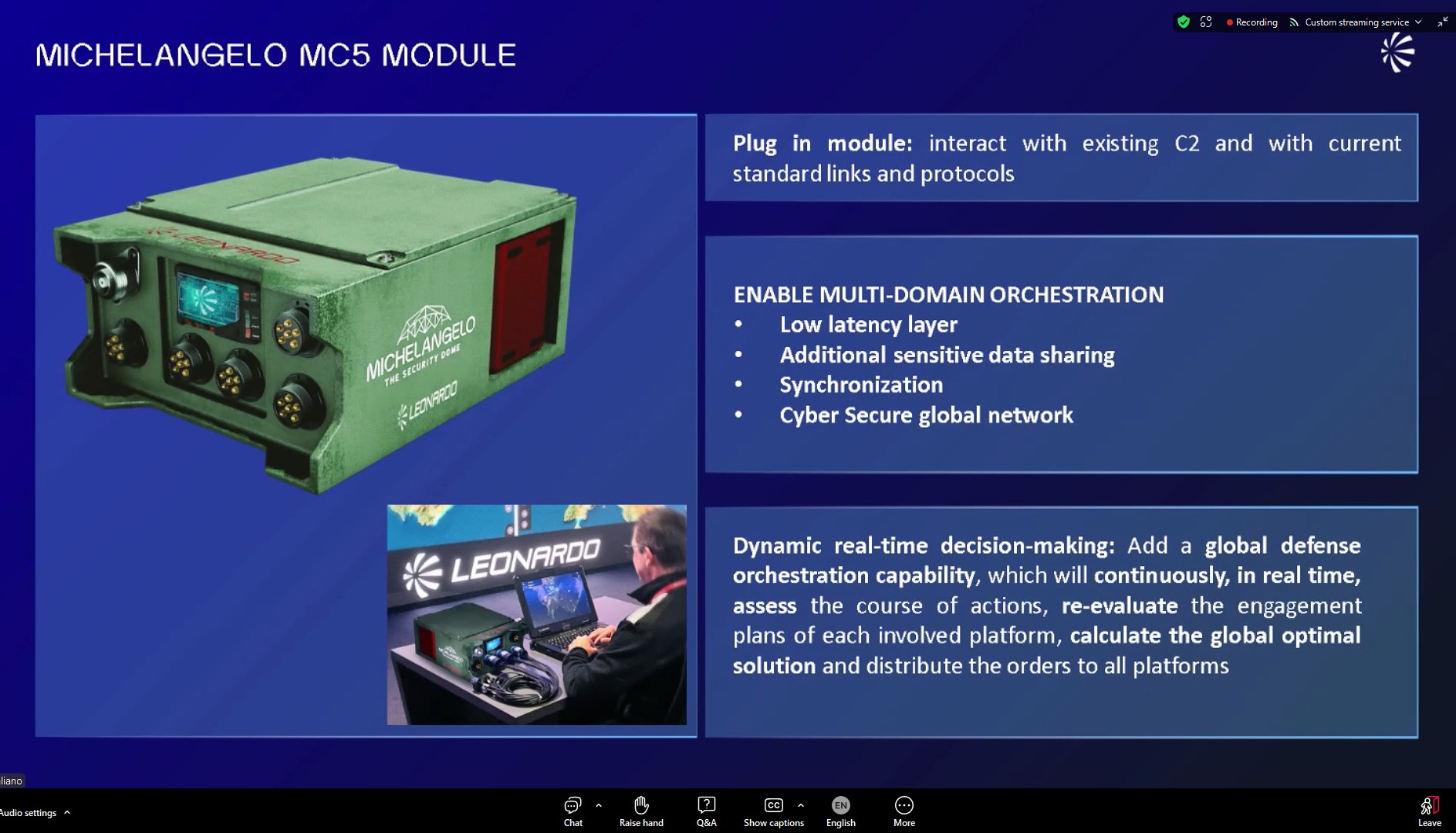

He argued that Leonardo has spent the past three years trying to rebuild a coherent portfolio for that purpose. He cited the new drone joint venture capable of lifting ten-ton payloads, the next-generation tank programme with Rheinmetall, the GCAP partnership with Japan and the UK on a sixth-generation fighter, and satellite programmes with France. Even so, he said, hardware is no longer the limiting factor. “The hardware is pretty much okay. What is missing to make sure this multi-domain approach can become interoperational is that platforms need to be interconnected. They need to communicate with one another and they need to be interchangeable.”

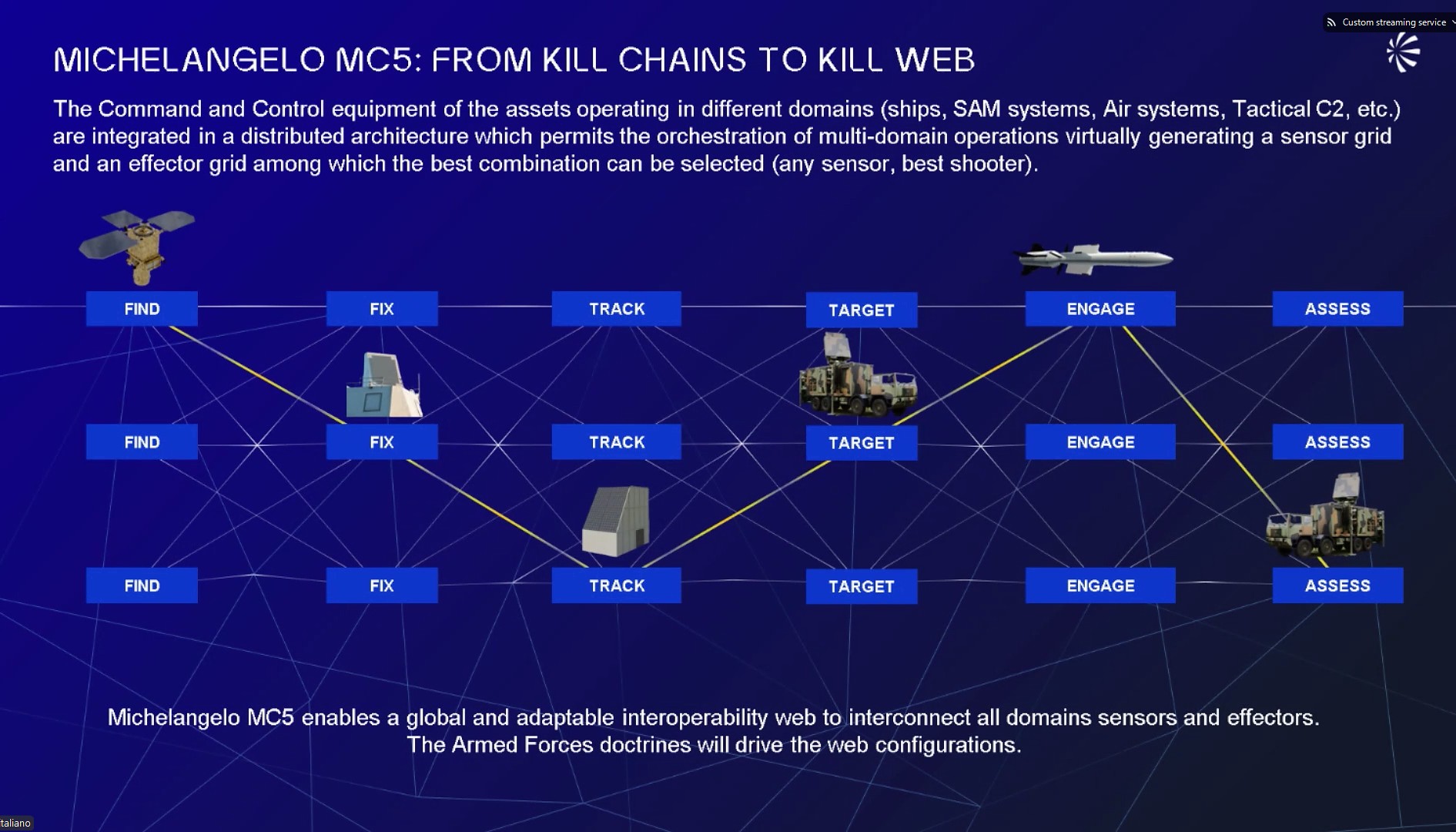

The operational argument Cingolani made was unambiguous. Europe must be able to move from the traditional kill chain to a distributed kill web. “We need to be able to see a threat, identify it, understand where it comes from, follow it, track it, and decide how to neutralise it,” he said. “It may be a ship, it may be a plane. What matters is the best possible option to stop that threat.” He compared the required behaviour to an orchestra, where capability lies not in the individual instruments but in their synchronisation.

To illustrate the stakes, he returned repeatedly to recent conflicts. “Young soldiers fitted a half kilo of explosives on drones designed for cameras connected to Starlink. They would pilot their drones through mobile phones and neutralise tanks, which cost 20 million euros.” He framed this as a marker of what comes next. “We think it’s over, but it’s only just the beginning. We have 18,000 cases of hybrid attacks every year.”

He also went into the physics of hypersonic systems. “Missiles which have a curve and their speed is 20 Mach, even 25 Mach. That is five or six kilometres per second. At one point during the trajectory they open up and attack different spots. Time matters.” His message was that European warning and interception times are inadequate. “Rome can be hit in a few hundred seconds, and currently, we would have a hard time defending ourselves.”

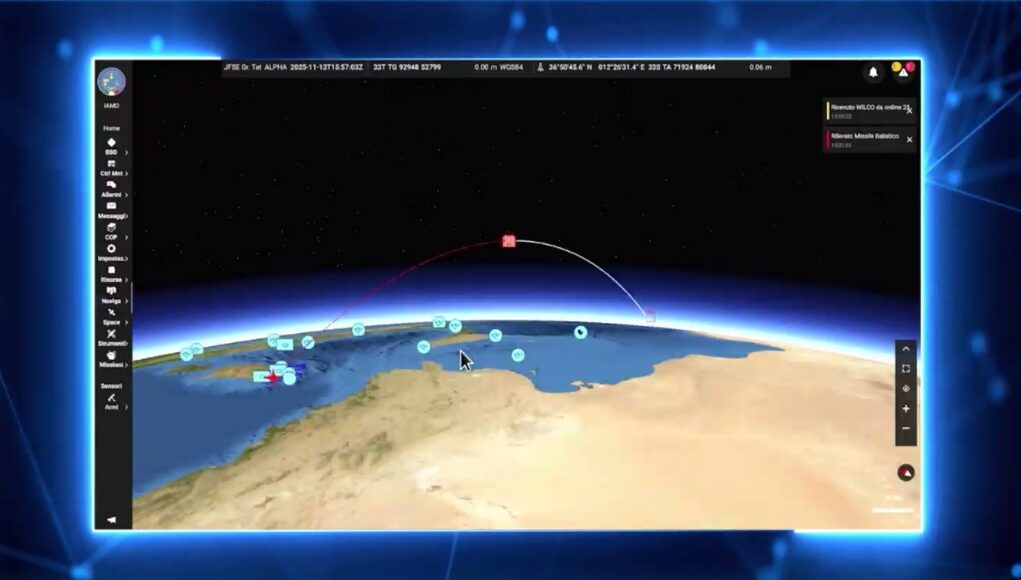

The technical requirements he set out for Michelangelo reflect that tempo. “We are talking here about hundreds of terabytes per second,” he said when describing the combined output of radars, satellites and infrared detectors. The problem is not sensor availability but human bandwidth. “When you have 180 seconds and you need seven people around the table to reach a conclusion, that may work for one missile but not for twenty.” Michelangelo therefore relies heavily on AI for sorting, storage, analysis and forecasting. “There will be an artificial intelligence which something we do now, which is done by human beings, will become even quicker.”

“You can’t expect Amazon or Google to manage these data. You want your own AI because it has to be supervised by our own person who is there to protect our European territory.”

Cingolani also positioned Michelangelo inside NATO’s command structure rather than alongside it. “Everything we are showing you is conceived to be compatible with NATO standards and compliant with command and control,” he said. The idea is to add a unifying layer that can accommodate assets from states with very different inventories. “If we have a country in Eastern Europe that doesn’t have money to buy the F 35 or the Patriot, if they have a missile somewhere, we can integrate it in the Michelangelo Dome by adding the ability to communicate following protocols and NATO doctrines.”

That inclusivity has a strategic purpose, “Those bubbles that you saw become one large dome,” he said when describing the proposed architecture. He argued that the density of the shield would only be credible if every participating state could contribute to the mesh.

“We have the data, we have the software, we have the AI, the hardware. We are the only ones who are ready to propose such an ambitious project.” He pointed to a recent exercise off Crete, which he said demonstrated Leonardo’s ability to intercept fast moving targets, as evidence that the company’s sensing and response systems meet NATO expectations.

He closed on the ethical argument that ran beneath his entire presentation. “We won’t use unethical AI. Our adversaries don’t care. If we want to respect the ethical rules of Western societies, we need these technologies.”

Michelangelo remains an architecture rather than a fielded system. The technical demands around latency, sensor fusion and cross-domain fire control are significant, and the political negotiation required to integrate national assets into a shared decision layer remains substantial. Still, the concept aligns with concerns already raised inside NATO about fragmentation and reaction time.

Leonardo is positioning Michelangelo as a practical accelerator to the EU’s Sky Shield effort rather than a rival architecture. Cingolani stressed that Michelangelo is an industrial programme with defined ownership and immediate work underway. “At the moment, there are some initiatives that are still on paper. It’s an industrial project that we’re working on, and hopefully the ITT will make it possible for us to speed things up with the implementation of the program.” He contrasted this with the slower dynamics of EU defence cooperation. “The timing of the European program is much longer, and as with all European programs, the difficulty is determining who will do what, whereas here we know who will be doing what, what the roles and responsibilities are.” He also acknowledged Europe’s stalled efforts.

“We know that there are some European programmes that have been so lengthy that they are now standing still, so we decided to do something at national level, and we will make it available to Europe. It is an open program. It is open even from a technological standpoint.” His message remained that Michelangelo is intended to strengthen, not displace, collective efforts. “What we are proposing is additional. It’s not replacing anything. We can develop new software and hardware which add communication layers on existing assets, and this would be useful for the other program as well.”

What remains is the question that Cingolani himself cannot answer: whether European governments will move beyond rhetorical support and fund the level of integration he is asking for.

“You can’t expect Amazon or Google to manage these data. You want your own AI because it has to be supervised by our own person who is there to protect our European territory.”

Absolutely.

To me this brings up the question of a multispeed NATO. If the shield only works by linking sovereign capabilities, how will it function when the chips are down? Would enough countries hand over their sovereign missile defences to a pan-NATO shield?

Maybe my interpretation but I think the idea is a solution evolving and adapting to European countries needs in line with NATO standards, not handing over to NATO the national missile defence.

Then, in the long run, Leonardo’s hope is obviously that this software solution, and the ESSI, and all other programmes, will converge into one integrated European shield.

I like the English Roberto uses for some parts of his delivery, different from how a native might say it.

Not a criticism, makes me smile as I have relatives there who would do the same.

On the overall concept, great. In reality, hmmmm.