A bump in domestic approval offers little reassurance for Putin’s military strategy.

Two recent studies by Western academics have concluded that public support for Vladimir Putin strengthened dramatically following Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, and again during its subsequent invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

One of these studies even found evidence that Western sanctions had improved the electoral fortunes of Putin and his ‘United Russia’ party (Ð•Ð´Ð¸Ð½Ð°Ñ Ð Ð¾ÑÑиÑ) in the 2018 presidential and 2016 parliamentary elections.

This article is the opinion of the author and not necessarily that of the UK Defence Journal. If you would like to submit your own article on this topic or any other, please see our submission guidelines.Â

Yet these findings are based on questionable data from a country where political freedom is severely constrained, and where a sizeable proportion of the electorate are woefully ill-informed by the government-controlled media they depend on for news.

Setting aside the increased likelihood of voter suppression and electoral manipulation, public opinion surveys and elections in countries practising ‘electoral authoritarianism’ are highly vulnerable to self-censorship and low levels of trust in ballot confidentiality.

Together these factors conspire to undermine any confidence Russia’s regime might place in apparent improvements in domestic approval attributed to Putin’s evolving military strategy.

Putin’s Political Vulnerability Amid Conflict

Instead, the pervasive uncertainties involved underpin the regime’s political vulnerability to both a prolonged conflict in Ukraine and to further ‘special military operations’ elsewhere.

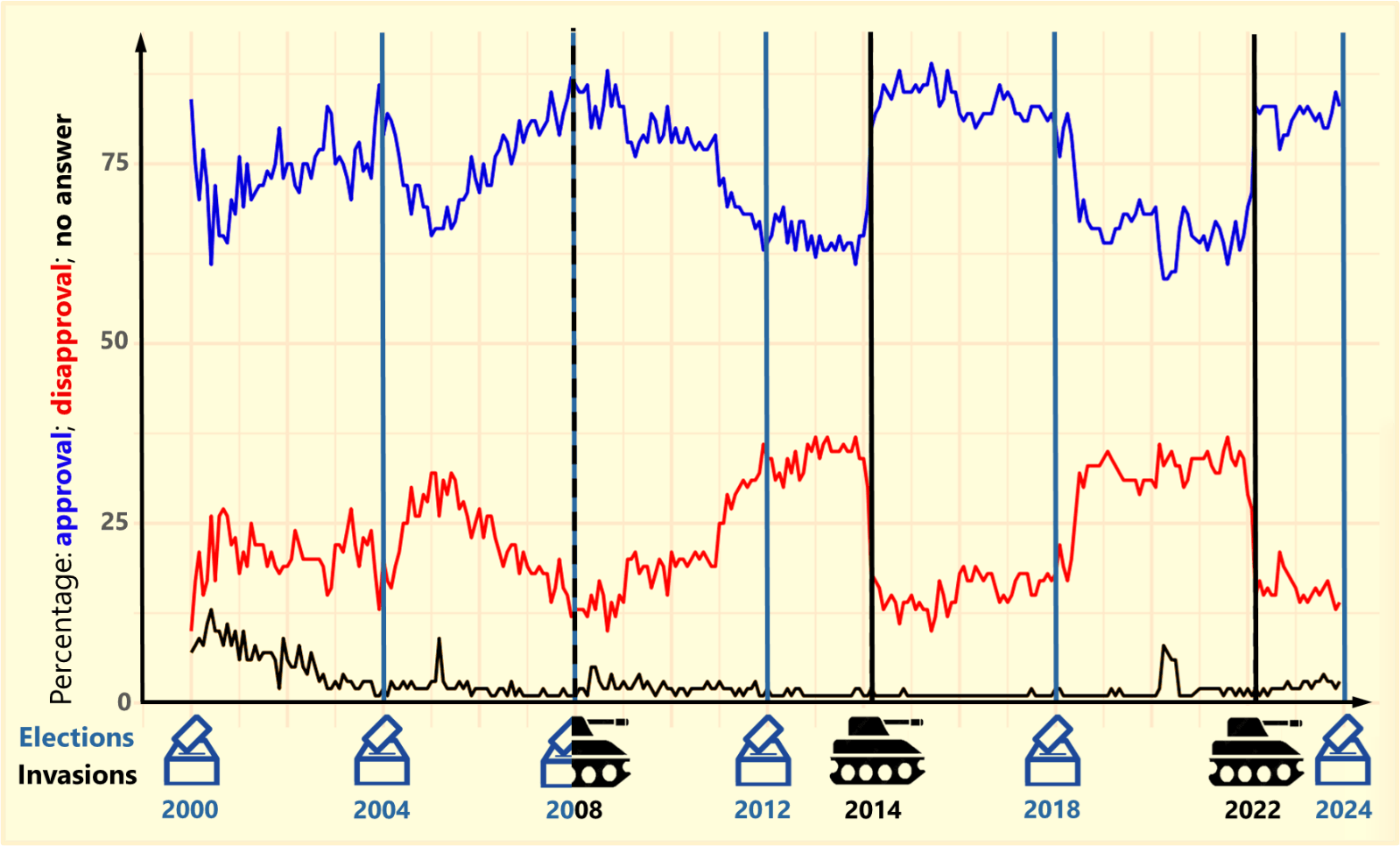

The first of these studies – published at the end of 2023 by academics from the University of Vienna and the JF Kennedy School of Government at Harvard – used public opinion data from inside Russia to reveal an almost instantaneous increase of around 20% in Putin’s personal approval rating following both the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the 2022 invasion of Ukraine (as evident in the graphic, below).

They argued that this was evidence of what is known as a “rally ‘round the flag†effect – one that has been observed during many crises across a variety of different countries in the past (including, for example, the so-called ‘Falklands Factor’, and the surge in public support for Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, following his country’s invasion by Russia on 24 February 2022).

[Graphic legend] Percentage of respondents asked the question “Do you approve the activities of V. Putin as the President (Prime Minister) of Russia?†who approved, disapproved or did not provide an answer. Data sourced from Russia’s Levada Center – an independent polling agency offering what a recent blog from the London School of Economics has described as the “most reputable public opinion data available in Russiaâ€.

Sanctions and Putin’s Electoral Gains

The second study – published as a Working Paper by the Munich-based CESifo network in March this year – explored the impact of Western sanctions following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea on voting patterns in subsequent presidential and parliamentary elections.

By comparing constituencies experiencing differing economic effects as a result of these sanctions, the authors were able to demonstrate that the worse the effects the greater the share of the vote received by Putin and other United Russia party candidates.

On the face of it, these studies support the view that increased regime support may have played a significant role in Putin’s rationale for both the illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine eight years later.

However, the dramatic increase in Putin’s domestic approval in 2014 is also likely to have been somewhat unanticipated. It may have therefore become an even more propitious incentive for further military action in 2022 when his domestic approval had waned (and briefly fell to its lowest level since he was first elected President in 2000).

Both interpretations seem plausible given the 2014 uplift in Putin’s personal approval was unprecedented in magnitude and duration. There is certainly no indication that a similarly profound shift in public opinion had occurred at any previous time in the 25 years that Putin has held high public office in Russia – the only possible exceptions being: the rapid decline in public approval that occurred in 2000; and a similarly rapid decline following his re-election as President in 2018. There is also little evidence of any improvement in popular support for Putin following Russia’s brief and successful campaign in the 2018 Russo-Georgian war – which concluded with Russian international relations largely unscathed despite the contested secession of two Russian-backed regions (Abkhazia and South Ossetia). To the contrary, Putin’s approval subsequently suffered a gradual but sustained decline over the six years that followed, only briefly (and modestly) interrupted by the Presidential election in 2012 when he was re-elected for his third term as President.

Media Control Fuels Apparent Support

It therefore appears likely that the dramatic and sustained increase in Putin’s approval ratings during the annexation of Crimea in 2014, reflected other changes that had taken place during his preceding years in office. These included the tightening of media censorship and increasing political repression – both of which will have accentuated any apparent uplift in public opinion in 2014.

If Putin’s regime mistook this as a genuine increase in support for the President – and his willingness to embark on military conflict with Russia’s neighbours – then it would not be surprising if the 2022 invasion of Ukraine had been viewed as a timely opportunity to rekindle his dwindling political fortunes at home. While the ongoing war with Ukraine has also been accompanied by a comparable (20%) bump in Putin’s approval rating – and one that has been sustained for two years thus far – it is too soon to tell whether this will also be sustained for (at least) four years, or will decline once more in the absence of further censorship, repression or renewed military action elsewhere.

Uncertainty in Russian Public Opinion

Such uncertainty may yet prove to be the least of Putin’s worries. This is because the data used by both of these studies are vulnerable to a number of intractable weaknesses and inherent biases which mean they are likely to have substantially overestimated popular domestic support for Putin. These biases include a tendency for individuals and groups who believe they hold unpopular or minority views to suppress or conceal their opinions in public. This is an effect known as the ‘spiral of silence’, and is an issue that has led some analysts to voice concern that such opinions are substantively underrepresented in Russian opinion poll data (and, potentially, in Russian election results).

Public opinion may also be woefully ill-informed and ‘soft’ in those contexts where access to independent news is limited or constrained. In this regard it is telling that the first of the studies examined for this analysis piece found that those Russian citizens who were dependent on State media for news were significantly more likely to trust the President than those with access to independent and uncensored sources.

For these reasons, even a pronounced bump in domestic approval may not provide the reassurance or confidence that Putin may need for a prolonged invasion of Ukraine, or to prosecute further military adventures primarily for political approval and regime survival at home.

He was always going to get more approval the longer it goes on because most Russians don’t really know their in a war at the moment, get some long range missiles down there necks and maybe he doesn’t get treated like a good leader.?

A lot of Russian soldiers at the front, are phoning home to tell family & friends not to believe the propaganda on TV.

I always find opinion poll questions unhelpfully vague, e.g. ‘do you approve the activities of your leader?’, which should logically lead to the response ‘which activity/activities in particular?’. The poll has no way to respond to having the nature of its questions questioned, which limits its value.

Interesting article. Thank you.

War is politics by other means…

With average life expectancy for men being around 67 (so far not really skewed by war deaths as far as Zi can tell) they must really love him!

In Russia, the idea that the leader would somehow be accountable to the people is totally alien and therefore surveys based on western principles are essentially pointless.