The UK was the third nation to develop nuclear weapons in 1952, after the United States and the Soviet Union.

The first five powers to join the atomic club also happen to be the United Nation Security Council’s permanent members with veto power.

On 30 August 1941, Prime Minister Winston Churchill authorised the programme to develop nuclear weapons becoming the first leader to approve a national nuclear weapons project.

Churchill was following the recommendation of the MAUD Committee, which was investigating the practicalities of building an atomic bomb and the destructive impacts of this new weapon. The research and development were named ‘Tube Alloys’, deliberately chosen to be meaningless ‘with a specious air of probability about it’.

Britain’s development of the weapon was progressing steadily but slowly. The cost of the Second World War was draining the resources needed to accelerate the programme. However, the feasibility of a nuclear weapon could not be disregarded. In 1943, Winston Churchill and American President Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed that the British and American research groups should merge into ‘a larger joint effort’, the ‘Manhattan Project’.

British knowledge and collaboration were essential to the Manhattan Project, as proved by the early exchanges between the MAUD Committee and the American programme in 1942. Britain’s information aided the Americans to be able to begin thinking about the ways to create a nuclear bomb, not whether it was a possible project. This close co-operation continued throughout the war, helping the Americans to reach the first detonation of a nuclear weapon on 16 July 1945 under the ‘Trinity’ code-name.

The Canadians were also deeply involved in the project, especially working alongside their British counterparts since the early days of the research. Canada’s contribution was linked to its close relationship with Britain. During the development and production of the atomic device, more than 30 facilities in the UK, the United States and Canada were used. The Canadian Government also participated in the 1943 Quebec Conference, where it was decided to join efforts with the United States.

Following the successful Trinity Test and the use of the new weapon against the Empire of Japan in August 1945, the nuclear co-operation between the United States and Britain would face a significant setback. The British Government considered nuclear technology to be a joint discovery, as its scientists were deeply involved in the Manhattan Project. Nonetheless, the debate in the United States concerning how the country should control and manage its new technology resulted in the ‘McMahon Act’ (officially the Atomic Energy Act of 1946). The McMahon Act effectively excluded Britain and Canada from nuclear information and technology sharing.

Implementation of the Act created a rift between the United States and the UK. The new rule was a severe control of ‘restricted data’, preventing the United States from providing information to Britain and Canada, in spite of the fact that both Canadian and British governments – before agreeing to join the Manhattan Project in 1943 – had made agreements with the American Government about the sharing of nuclear technology.

The accords between London and Washington were expanded and developed further in the Hyde Park Agreement of 1944, signed by Churchill and Roosevelt. This relevant document was lost in Roosevelt’s papers after his death in 1945, and when British officials mentioned it, their American counterparts were unaware until the agreement was finally found. In 1952, Senator Brien McMahon after knowing about the Hyde Park Agreement told Churchill that ‘if we had seen this Agreement, there would have been no McMahon Act’.

Therefore, being effectively excluded from the technology and research it was involved since 1943, the British Government decided to develop its own nuclear weapons. In 1947, the Attlee Government resumed an independent nuclear programme known as ‘High Explosive Research’. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union became the second nation to join the ‘atomic club’ after a successful test with a nuclear device in August 1949.

The UK successfully tested its atomic bomb on 3 October 1952 during the second tenure of Churchill as Prime Minister. Operation Hurricane was the codename for the test of the first British nuclear device, which occurred in the Monte Bello Islands in Western Australia. The Admiralty suggested the location and the Australian Government formally agreed that Monte Bello could become the testing site in 1951.

One consideration that marked Operation Hurricane was the British Government’s fear that an atomic device could be smuggled aboard a ship and detonated near a British port-city. Thus, the Operation was taken as a chance to test not only an atomic weapon but also the effects of a nuclear device detonated inside the hull of a vessel and below the water line. The frigate HMS Plym (K271) was chosen as the detonation platform anchored 35 metres off Trimouille Island. Later, Britain engaged on a series of nuclear trials in Maralinga, Australia.

With the success of a British made and designed nuclear weapon, the UK became the third nuclear power after the United States and the Soviet Union. However, four weeks after Operation Hurricane, the United States successfully mastered and tested a new technology: the hydrogen bomb (technically called thermonuclear or fusion weapon). In short, a thermonuclear weapon is a ‘second-generation’ design for nuclear devices. Its destructive power is vastly superior to ‘first generation’ atomic bombs. Differently from the first nuclear weapons that are fission bombs, thermonuclear weapons are a combination of fission and fusion reactions.

The British Government formally decided to develop a hydrogen bomb in 1954 following news that the Soviets had mastered the technology. Britain’s efforts came to fruition during Operation Grapple, a series of tests on and around Christmas Island and Malden Island. The first test at Malden Island on 15 May 1957 was hailed as successful. In fact, this test did not work as expected, and the first British hydrogen bomb known as Grapple X was successfully detonated on 8 November 1957. Nevertheless, most of the yield came from traditional nuclear fission rather than fusion.

In April 1958 a third test using a design known as Grapple Y finally meet what British scientists wanted: most of its explosive yield came from its thermonuclear reaction, and its yield was closed calculated and predicted; these factors displayed that British designers mastered the technology. Grapple Y remains the UK’s largest nuclear weapon ever tested. Between August and September 1958, Britain would perform four detonations as part of Grapple Z tests; two of these detonations were atmospheric tests.

Mastering the new generation of nuclear weapons approached Britain and the United States to resume co-operation. In the same year, the McMahon Act was amended to allow nuclear collaboration between the two nations. The cornerstone of Anglo-American co-operation on nuclear defence issues was signed; known as the Atomic Energy for Mutual Defence Purposes or only ‘Mutual Defence Agreement’.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, the UK relied solely on air-launched nuclear weapons. Britain’s Blue Danube free-fall bomb was its first operational atomic device, which was delivered on V-bombers of the Royal Air Force (RAF). The thermonuclear weapons were operational in 1961 when the Yellow Sun Mk.2 – with ‘Red Snow’ warheads – entered service. The Blue Steel became Britain’s first nuclear missile also launched from a V-bomber. Its further development was cancelled in favour of participating in the American Skybolt programme. However, one year after Britain had joined the American air-launched stand-off missile programme it was cancelled by President Kennedy due to delays and cost overruns.

Skybolt’s unexpected cancellation in 1962 left the UK with a nuclear deterrent dependent of the V-bomber force. The concern was that since the late 1950s, the V-bombers were considered vulnerable to new Soviet air defences. It is worth mentioning that before adhering to Skybolt and cancelling further investments on the already cited Blue Steel, the British Government even considered a solution through the ‘Blue Streak’ ground-launched intermediate range ballistic missile. The vulnerability of a silo-based missile system to a pre-emptive attack led to its cancellation.

In 1962, Britain faced the risk of having an inefficient and unreliable nuclear force. A solution was found through the Nassau Agreement, signed between the UK and the United States in the same year. The agreement stated that the American Government would make the Polaris missile system available to Britain. In 1963, the Polaris Sales Agreement was formalised, and the Royal Navy was about become the second branch of the British Armed Forces to receive the nuclear deterrent. The Resolution-class of ballistic missile submarines was built as part of the Polaris programme and it remained in active service from 1968 to 1996 when the Vanguard-class carrying Trident II came into service.

Polaris’ warheads were designed and built in Britain. The device comprised an enhanced version of the WE177, the main air-dropped bomb in British service. Later, in 1982, the ‘Chevaline’ warhead would enhance Britain’s strike capability. Chevaline development envisaged improvements on the penetrability of British warheads used by Polaris. It was a response to the improved Soviet anti-ballistic defences around Moscow and had as the objective that at least one warhead would penetrate the Soviet defences.

The system used decoys and ‘penetration aids’ offering many indistinguishable targets that the task of the anti-ballistic missile defences would become overwhelming. The Chevaline project was revealed in 1980, after secrecy that survived four different governments. Its operational capability was declared in 1982. Although a British technological success, the programme to enhance Polaris’ capabilities was an expenditure burden. Chevaline was retired in 1996.

While Chevaline was entering service and giving new credibility to the Polaris system, Margaret Thatcher’s government revealed that the American missile system ‘Trident II D-5’ would replace Polaris. Similarly to what proceeded with Polaris, Britain would build the new submarines and warheads.

The Vanguard-class consists of four nuclear-powered submarines each one is capable of carrying up to 16 missiles and each missile can carry up to eight warheads. Patrols began in December 1994, and almost two years later the ‘Polaris era’ ended at the decommissioning ceremony of HMS Repulse – the last active Resolution-class submarine – in August 1996 at Faslane. In 1998, the WE177 free-fall thermonuclear weapons were decommissioned, leaving the four Vanguard submarines as the sole platforms for Britain’s nuclear weapons.

According to the British Government, ‘since 1969, the Royal Navy has delivered the nuclear deterrent under Operation Relentless’ and having four nuclear-armed submarines guarantees that at least 1 of 4 vessels is on patrol ‘at all times’. Accordingly, HM Government declares that ‘an independent centre of nuclear decision’ makes clear to any foe that ‘the costs of an attack on UK vital interests will outweigh any benefits’.

The nuclear co-operation with the United States is a source of many misunderstandings concerning Britain’s sovereign position over its nuclear deterrent. This relationship does not compromise the ‘operational independence’ of the British nuclear force.

According to the British Government, ‘decision making and use of the system remains entirely sovereign to the UK’ and only the Prime Minister can give the authorisation to launch nuclear weapons, ‘which ensures that political control is maintained at all times’. The Vanguard submarines ‘operate readily without the Global Positioning by Satellite (GPS) system and the Trident D5 missile does not use GPS at all’.

Moreover, under the 1958 Agreement, the American Government supplies Britain with the ‘delivery systems’.

The design, manufacture and maintenance of British warheads are a solely British responsibility. The Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) is the national agency responsible for designing and manufacturing the British nuclear weapons and fitting these weapons into the delivery systems.

At its peak in the 1970s, Britain’s nuclear stockpile reached 520 warheads. Following the end of the Cold War, the British Government reduced the number of stockpiled warheads to around 215 in 2016; the strategic arsenal was 120 in the same year. The end of the Cold War also influenced the suspension of British nuclear tests.

On 26 November 1991, the last British nuclear test was conducted at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) through codename ‘Julin Bristol’. In all, Britain was responsible for 45 nuclear tests – not including ‘subcritical testing’ – of which 24 were conducted at the NTS. Five years after Julin Bristol, the UK signed the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT).

However, subcritical British nuclear tests in America continued throughout the next decade; the last one was ‘Krakatau’ in February 2006. Any type of tests involving nuclear materials and chemical ‘high explosives’ that purposely result in no yield receive the ‘subcritical’ denomination. Its name refers directly to the lack of creation of a ‘critical mass’ of fissile material. Under the interpretation of the CTBT, they are the only type of tests allowed.

Since the withdrawn from service of the tactical WE 177 bombs in 1998, the Trident II has been the only nuclear weapon delivery system that is operated by Britain. Therefore, not renewing Trident would probably mean that Britain would cease to be a capable nuclear power affecting its status as a great power, its position as a permanent member of the Security Council, its capability to defend its vital interests and, consequently, its special relationship with the United States.

These arguments were considered and influenced the decision of Parliament when the House of Commons voted in favour of the programme renewal in 2016. A significant majority was achieved with 472 MPs voting in favour and 117 against.

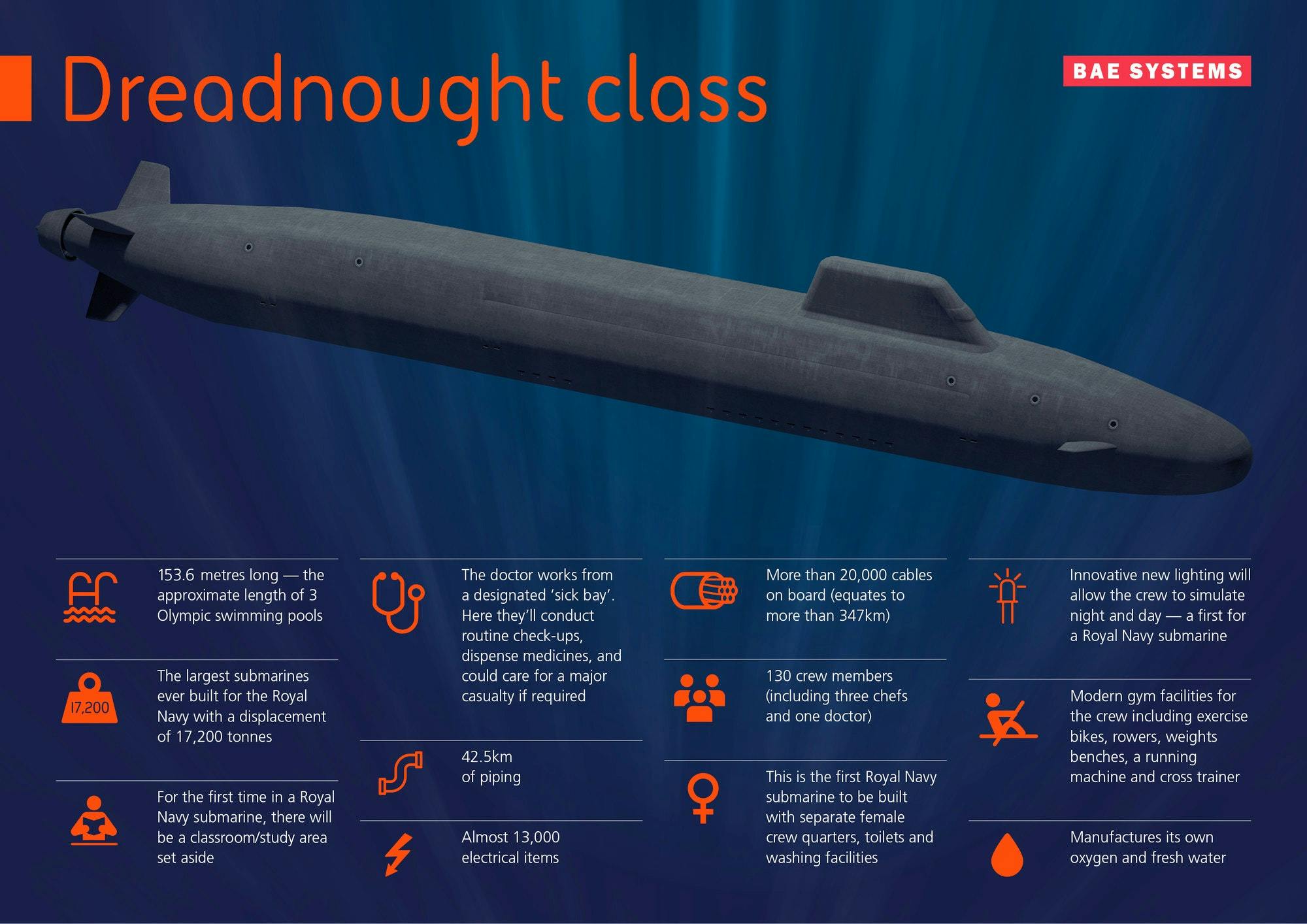

Like their predecessors of the Vanguard-class, the Dreadnought-class of ballistic missile submarines will carry Trident II D-5 missiles; accompanied by a life-extension programme for the D-5. The first submarine will be named Dreadnought, and the next three will be Valiant, Warspite and King George VI. BAE Systems Maritime Submarines started construction of the first hull in late 2016 at the Barrow-in-Furness shipyard.

The first submarine is expected to enter service in 2028 and the other three are planned to the early 2030s. The Dreadnought-class is set to replace the Vanguard-class as the future of Britain’s continuous at-sea deterrent (CASD) with a service life of roughly 35 years.

Each submarine of current Vanguard-class could carry up to 16 Trident II missiles and 48 warheads at any given time; having a maximum of 192 independently targetable warheads available. However, following the end of the Cold War, these numbers have been decreasing steadily. Since the 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review, the total number of warheads deployed by the four submarines is no more than 40 and the Trident II missiles were reduced to eight per submarine.

The number of warheads is superior to the number of missiles due to the Multiple Independently Targetable Re-entry Vehicle (MIRV) capability of Trident. Beyond the strategic deterrence role, the Vanguard-class also have a sub-strategic ability, which means that nuclear weapons with smaller explosive power can also be deployed by the submarines.

The number of warheads is superior to the number of missiles due to the Multiple Independently Targetable Re-entry Vehicle (MIRV) capability of Trident. Beyond the strategic deterrence role, the Vanguard-class also have a sub-strategic ability, which means that nuclear weapons with smaller explosive power can also be deployed by the submarines.

Therefore, in spite of economic difficulties, the UK was one of the pioneers in the researches that eventually contributed to the successful Manhattan Project and a British-made and tested nuclear weapon in 1952, becoming the third nation to enter the ‘nuclear club’. British designs and ideas were well regarded by the Americans when co-operation was resumed and the Mutual Defence Agreement of 1958 became one of the most relevant aspects of the ‘special relationship’.

Moreover, the British Submarine Service is an example of professionalism and efficiency recognised throughout the world, and the submarine-launched ballistic missile is regarded as the most secure way of maintaining a nuclear deterrent.

Additionally, as a ‘nuclear state’ – with a credible delivery system – the UK reinforces its claim as a relevant country in the international arena with global interests and capabilities.

An interesting and informative article, thank you. It’s the first time I have heard of the ‘Hyde Park Agreement’ and it’s temporary loss.

Ditto to Pauls comments, thank you for the article.

What the author has missed is the use of the WE177 as a multi-purpose warhead. It could be fitted as part of a depth charge, torpedo, anti-ship missile and surface to air anti-aircraft missile. It was designed so that the yield was controllable and could be dialled in before it was installed.

The inert training freefall bomb was cleared on lot of UK aircraft, including helicopters, ranging from Nimrod to Sea Harrier. It could even be fitted with the Paveway kit, but it would be a very brave person on the ground to keep the designator on the target!

Although, we technically scrapped WE177, the knowledge is still there with AWE to rebuild or even build an enhanced version if necessary, should there be a future requirement.

The RN “Bucket of Sunshine” WE177 was a warhead in a bomb shape as the picture above shows. The bomb did have variable yield through being a boosted design, along with sub surface, surface and air burst options.the selections where set using castillated keys that resembled the keys everyone had onboard for their kit lockers.. Apparently the key manufacturer had guaranteed that the warhead keys where unique and Jack couldn’t dial up the settings with his locker keys. With the 2 man rule that would not have been possible anyway but would have been interesting to see if it was true!

It could be dropped by everything from a Wasp helo to a Tornado. You Could depth charge it, lay down delivery, lob deliver and parachute delivery, It was though very 1950/60s tech. Lots of dark green test boxes that looked like they where from a shonky syfi movie.

Being boosted it also had a shelf life as the tritium inevitably decayed down meaning it needed replacing shore side at AWE on a mandated basis.

Personally it was a pain in the a**e to look after and maintain but it was needed for a job and it did that. Random Type 22 frigates where peacetime carriers for it. I for one was glad to see the back of it. No more coming into work on a Sunday with the jetty closed off, tooled up RM and Mod plod everywhere to bring on a big green 2 ton container of “eggs”.

And it would have been a very brave, or foolish Wasp pilot who dropped one. Having done time in the simulators at Dryad it was generally reckoned that the chances of a helo clearing the area of an NDB blast were vanishingly small. Luckily I was a fishhead.

Construction of the the first of the class started in 2016 and it will first enter service in 2028? I know it’s a new and probably complicated design but that still seems an absolutely staggering amount of time. They’re costing I believe £11 billion for four of the class also, which will have annual running costs of £2 billion (which seems even more absurd). I can’t help but feel we’re being sucker punched here.

Surely the MOD/BAE are dragging this out hence it taking up much more time and money? Can somebody with more knowledge on this enlighten me please?

“Construction” is a bit of an exaggeration. They’re not actually building the sub itself yet, the DDH can only hold 3 hulls at a time and the last 3 Astutes are in there still. Production has only started on long lead items that are already finalised in the design (like the Common Missile Compartment)

I stand corrected, thanks Callum.

Could these not be a good, higher capacity complement to the Astute Class if we maxed it out with tomahawks? If they’re quiet enough to be SSBNs they’re quiet enough to be anything else I presume (maybe even quieter than an Astute?)

Could increase the build rate and hopefully get the unit price down a fair bit?

Theoretically, you could use them as SSGNs, but with only 4 boats detaching one just to throw some cruise missiles would effect scheduling and potentially mean we don’t have a deterrent boat at see. It’s not worth it.

Build rate isn’t going anywhere for two major reasons: first, there is physically no capacity to, the last Astute boats are still in build and Barrow has no spare capacity. Second, faster build rates require a lot more money in the short term, which the MoD doesn’t have (remember they still have a ~£7bn hole in their 10 year budget plan)

Thanks for the insight.

Presumably it is completely impossible to build extra SSGNs in addition to the 4 SSBNs?

Completely impossible, I suppose technically not? Given that we’re right at the start of the Dreadnought build and the CMC is designed to accommodate cruise missiles as well, in theory you’d “simply” just need to order additional Dreadnoughts. Historically the RN always wanted more than just the 4 bombers because it added redundancy (and in today’s form an extra boat or two would allow deployment of an SSGN that could still cover deterrent duties if needed), but even back during the original Polaris buy the budget wouldn’t accommodate it without major cuts elsewhere. Another issue is that the Astutes are designed with a 25-year core life, and by the end of the current planned Dreadnought build we should be starting the new hunter killer build, so there could theoretically be some scheduling issues.

As a feasibility study, an increased purchase of Dreadnought to enable an SSGN tasking is technically possible, but economically and politically highly unlikely, and from the RN’s view not a high priority (remember a single Dreadnought is probably the price of half a dozen frigates or several squadrons of Lightnings, both of which would be more useful)

What scares me is that unless we want the fleet to halve in number again due to the increased price of equipment, we’re going to have to effectively buy “twice” as much next generation equipment as we have now to maintain numbers at the same level.

Unless we turn the next generation of attack subs into sub-drone carriers, and turn our frigates into micro-carriers for drones to increase their reach. Maybe?

If we can’t do that, then the navy will half in size.

I do fear we are running down the deterrent to the point where it no longer deters.

Glad to see the Canadian contribution properly acknowledged – always stalwart in its support for the UK and our greatest ally, with all due respect to our ANZAC friends. Bit disappointed with the limited references to Labour’s support and for the deterrent. Chevaline was instigated by the Labour government, for example.

The ability of the RN to keep one, sometimes two, boats at sea is a tribute to the RN.As Peter Henessy’s ‘The Secret State’ second edition noted, the USN is very impressed with the achievement. Four boats – one at sea, one preparing, and one in refit, with one as a spare for emergencies/accidents – five would ensure two on patrol.

The article should have made clear that Polaris was essentially a city destroyer, without any accuracy as a counter force weapon, though while the use of Trident (initially the C4 version) as counter force by the UK alone against the USSR was highly improbable this should be made clear.

The Empire was always there.

I haven’t read the full article, but being pedantic, the authors opening comments are slightly ambiguous and open to misinterpretation. It is correct the the Peoples Republic of China (China) tested their first nuclear weapon in 1964, but they did not become a member of the “Big 5” on the Security Council, as this post was held by the Republic of China (Taiwan) until 1971. The original five members where the “five” victors after the 2nd WW.

Pedantic perhaps, but had China not been invaded by Japan, it is likely they would have remained neutral and therefore would probably not been offered a permanent seat, and it is possible that it may have originally only consisted of 4, with possibly India joining in 1947 after it got independence.

Missed out Project Emily and the PGM-17 Thor missiles.

A big part in our early nucleardefence history.