How we discovered the wreck of a torpedoed British ship after a 109-year mystery.

A British cargo ship which was torpedoed and sunk during the first world war has finally surrendered its 109-year-old secret.

The SS Hartdale was steaming from Glasgow to Alexandria in Egypt with its cargo of coal when it was targeted by a German U-boat in March 1915. The location of the ship had long been a mystery, but my colleagues and I have, at last, pinpointed its final resting place.

This article is the opinion of the author Michael Roberts, Bangor University and not necessarily that of the UK Defence Journal. If you would like to submit your own article on this topic or any other, please see our submission guidelines.

The old adage that we know more about the surface of the Moon and about Mars than we do about Earth’s deep sea may no longer hold entirely true. But the reality is that we still have a great deal more to learn.

Even our seemingly familiar shallow seafloors near the coast are relatively poorly mapped. Many people may think such areas are well explored, but there are still fundamental questions we can’t answer because detailed surveys haven’t been done.

The UK’s surrounding seas hold a vast underwater graveyard. Thousands of shipwrecks, from centuries of trade and conflict, litter the seabed like silent historical markers.

Surprisingly, even though we know where many wrecks lie, their true identities often remain a mystery. But the Unpath’d Waters project is now linking maritime archives with existing scientific data to help reveal some of these secrets.

History meets science

Scientists are using detailed sonar surveys from more than 100 shipwrecks west of the Isle of Man. Combining this underwater data with historical documents from around the world, researchers are piecing together a massive nautical jigsaw puzzle, finally revealing the true stories of these sunken vessels.

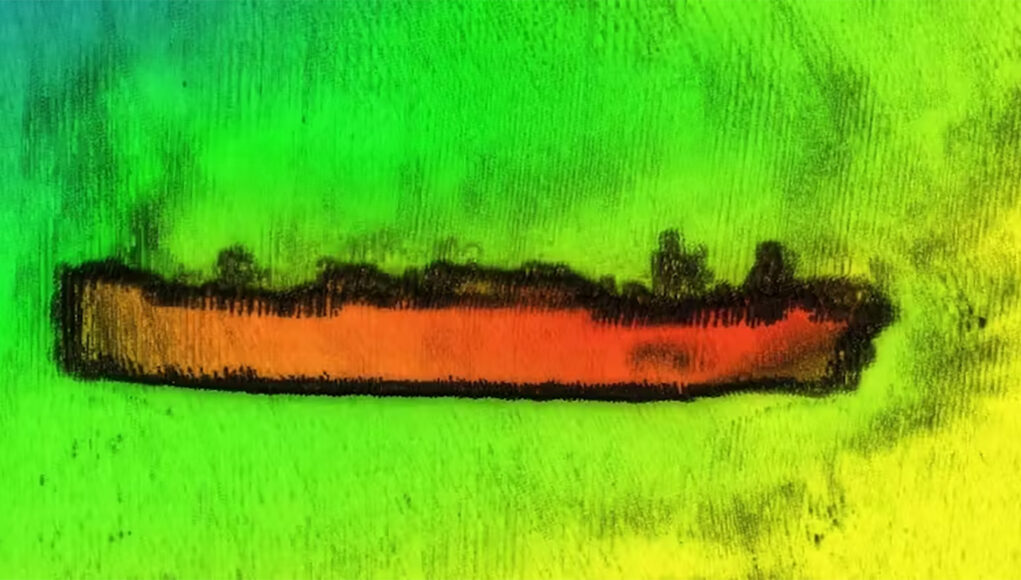

The first successful identification to be made as part of this work is that of the SS Hartdale. When the 105 metre long vessel was torpedoed at dawn on March 13 1915 by the German submarine U-27, two of its crew were lost and its final location remained unknown.

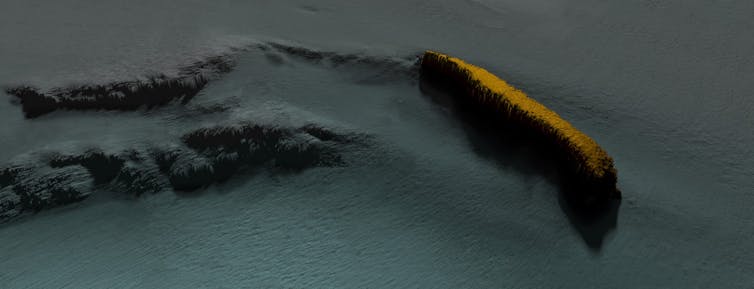

Researchers began by scanning known wrecks in the attack area, narrowing the possibilities down to less than a dozen. Then, they compared wreck details with official records and diver observations, eliminating candidates one by one until the SS Hartdale emerged as the perfect match. The vessel is lying at a depth of 80 metres, 12 miles off the coast of Northern Ireland.

The Lloyd’s Register Foundation

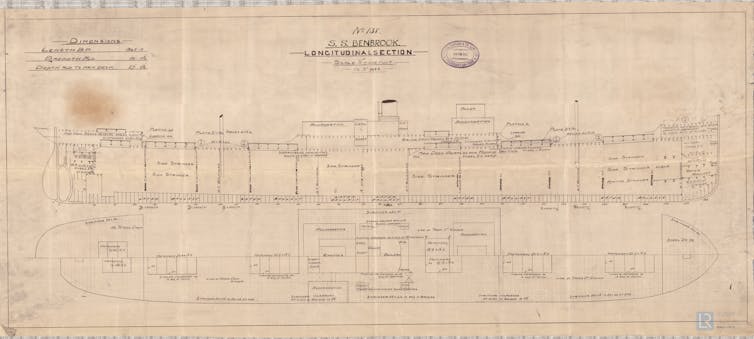

Important details about SS Hartdale are available online via the Lloyds Register Foundation. This includes plans for the construction of the ship, formerly known as Benbrook, built for Joseph Hault & Co. Ltd in 1910. This information, together with eye-witness accounts reported in the national press at the time, have proved to be crucial in confirming the wreck’s identity.

The US historian Michael Lowrey also provided the project team with a translated copy of notes extracted from an official German account and scans of U-27’s official war diary made by its commanding officer, Kapitänleutnant Bernd Wegener. These contained descriptions of the events leading up to the sinking, coordinates for the attack and the exact location on Hartdale where the torpedo struck its hull – a detail strikingly confirmed by the sonar scan data.

Armed with this compelling evidence, the research team reached a definitive conclusion. The only viable candidate for the SS Hartdale was a previously “unknown” 105 metre long wreck. It has been lying just a few hundred metres to the south of where U-27 launched its fatal attack.

Unrestricted submarine warfare

Following its attack on Hartdale, the U-27 went on to play a prominent role in how naval warfare developed during the rest of the first world war. This came during a period of escalating tension in 1915.

Following the sinking of the British ocean liners, RMS Lusitania in May, and the SS Arabic in August of that year by U-boats, the way the war at sea was being conducted became increasingly heated and controversial.

Shortly after the SS Arabic was sunk by a different U-boat, the U-27 was itself attacked and destroyed by the Royal Navy Q-ship HMS Baralong. Q-ships were heavily armed merchant ships designed to lure submarines into making surface attacks.

The surviving German sailors, including U-27’s commanding officer, were then allegedly executed by British sailors in front of American witnesses. It has since become known as the “Baralong incident”.

German outcry over this event combined with other factors contributed to the start of “unrestricted submarine warfare” by Germany in February 1917. This meant that warnings were no longer issued to merchant vessels prior to U-boat attacks and loss of life was significantly increased.![]()

Michael Roberts, SEACAMS R&D Project Manager, Centre for Applied Marine Sciences, Bangor University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Really interesting project, one I’ll keep an eye on- thanks for sharing UKDJ! Wouldn’t have found out about it otherwise.

Bangor are still at it. Interesting. Been a few years since they collaborated with the RCAHMW’s U-Boat Project.

However, the primary reason for Unrestricted Submarine Warfare was a combination of Jutland depriving Germany of a balanced fleet for 6 months (the lost light cruisers were only replaced around mid-November, with battlecruisers repaired by mid-October) and the onset of the worst German winter of the war- “the Turnip Winter” leading to calls to tighten the blockade of British trade. The Admiralstab knew that a similar outcome as Jutland could keep the HSF out of action for another 6 months, which would have dented German morale even further. Thus, like the French before them, they pirouetted from fleet action to commerce warfare, with the usual result of failure (at high cost due to the RN’s convoy reluctance, but they got there in the end).