In an exclusive interview, Paul Sweeney MSP, former shipyard worker and current convener of the Cross-Party Maritime and Shipbuilding Group, warned that Scotland’s shipbuilding industry faces decline unless long-term investment and a unified national strategy are prioritised.

Scotland’s shipbuilding sector has long been a cornerstone of the UK’s defence industry, but it is also at a critical crossroads.

Sweeney, a passionate advocate for shipbuilding, shared his insights into the sector’s challenges, the opportunities for its future, and the role of government and policy in ensuring its long-term sustainability.

The Strategic Importance of Scottish Shipyards

Paul Sweeney began by stressing the central role of Scotland’s shipyards in the UK’s defence infrastructure and their broader importance to Europe’s naval capabilities:

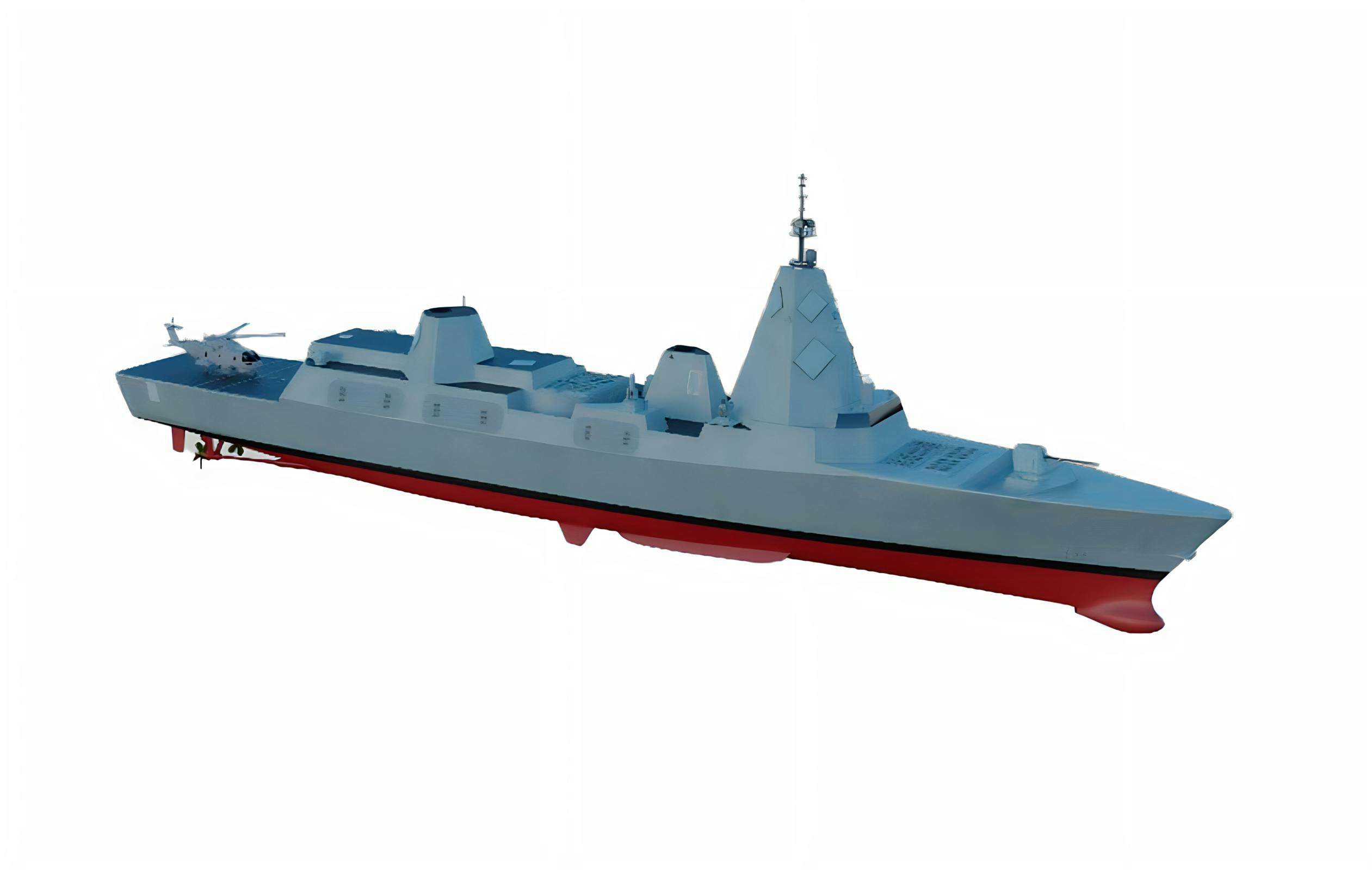

“The concentration of ship design expertise in Scotland is absolutely crucial to European and NATO defence capability. Between the shipyards in Glasgow and Rosyth, it probably comprises the biggest centre of excellence for naval architecture in Europe, along with Strathclyde University, which is a world-leader in the field.”

Recent upgrades at major shipyards, including the Clyde and Rosyth facilities, were praised as a step in the right direction:

“With the progression to fully covered indoor ship assembly at both sites, that introduces a major opportunity to improve productivity even further.”

However, Sweeney pointed out that systemic inefficiencies remain, particularly in procurement processes:

“The main thing that’s holding the industry back at the moment, is the flawed procurement processes that the Ministry of Defence and the UK Government continue to persist with, which artificially constrain the efficiency of the shipbuilding operation.”

Reforming Procurement for Long-Term Stability

When asked how UK procurement policies could be improved to support Scottish shipyards, Sweeney called for a shift towards longer-term planning and funding:

“We need to break out of annualised funding constraints, and we need to look towards long-term shipbuilding programmes. The replacement rate for each type of vessel should be known and should be financed on a permanent, rolling basis, and that would provide a much greater level of production stability for the industry to invest for the long term.”

Reflecting on the abrupt end of the Type 45 destroyer programme, he highlighted the consequences of short-term thinking:

“To curtail the programme at six ships was a disaster for sustaining skills. We ended up with a very ragged end to that programme in 2013 that culminated in significant redundancies in Glasgow and the closure of the relatively modern former Vosper Thornycroft shipbuilding operation in Portsmouth.”

Sweeney also noted the importance of consistent demand for maintaining skills and improving industrial processes:

“Short-term procurement decisions made over a decade ago continue to haunt the industry. Much like when I first started working in the shipbuilding industry around 2010–11, decisions in the mid-1990s to curtail apprentice recruitment due to uncertainty over where batches of the Type 23 Frigate would be built meant that what was then Yarrow Shipbuilders in Scotstoun ended up with a very lopsided demographic in its workforce by the time I started. We had lots of people in their 50s and lots of people in their 20s, but not many people in between.”

Leveraging Defence Demand Signals

One of the most promising strategies Sweeney highlighted was the potential for leveraging defence demand to drive commercial opportunities. He proposed a UK shipbuilding model inspired by the Italian Fincantieri group, which integrates multiple shipyards and the wider supply chain to achieve national competitiveness:

“We should collaborate across the shipbuilding industry so that we develop more of an Airbus model, where each [shipyard] has a specialism, and they contribute to achieving a collective competitive advantage as a country and as a total shipbuilding enterprise… much like the Italians do with the Fincantieri group.â€

“It was a huge strategic mistake for the British Government to break up and sell the British Shipbuilders group in the late 1980s. It was a classic case of British inability to persevere to achieve long-term industrial success, despite initial difficulties in restructuring the industrial base. Indeed as a former director of British Shipbuilders, Bill Scott said in the early 1990s, ‘At the point British Shipbuilders was starting to become effective, it was terminated.’ We’ve seen a similar story play out more recently, with the collapse of the fledgling Harland & Wolff group due to a lack of UK Government support meaning that it has now, rather ironically, come under the control of Spain’s state-owned national shipbuilding champion, Navantia. Rather humiliatingly, we will now need to rely on the Spanish to teach us how to do commercial shipbuilding effectively, given that the UK squandered its long-established advantage around 40 years ago.â€

A revived British model that emulates the Italian or Spanish shipbuilding industrial base would not only create a more coherent, unified national shipbuilding strategy but also enable Scotland and the UK to capitalise on the existing defence order pipeline. Sweeney explained that a stable demand signal from defence is essential for enabling long-term investment:

“The replacement rate for each type of vessel should be known, financed permanently, and linked to a coherent shipbuilding strategy across all British shipyards. This kind of stability would create a strong incentive to optimise design and production processes, drive down unit cost, and allow us to fully leverage the defence demand signal.”

Sweeney emphasised that this approach could avoid many of the inefficiencies currently plaguing the industry, such as fragmented programmes and stop-start production cycles. Reflecting on past lessons, he remarked:

“We shouldn’t continue down the path of introducing inefficient artificial competition to what is most efficiently managed as a natural monopoly at a national level. Generating sufficient, sustainable volume through our core shipbuilding sites with a single, repeatable design platform is key to achieving stability, efficiency, and global competitiveness.”

He also addressed the broader challenges posed by past decisions, such as the failure to properly integrate commercial shipbuilding opportunities with defence demand:

“We need to use the whole cross-government shipbuilding pipeline—including projects like lifeline ferry procurement—to optimise capacity across the Scottish shipbuilding supply chain. That kind of synergy would provide a much-needed boost to our ability to compete in the commercial sector. Some projects have shown its potential, such as the partnership between naval shipbuilder VSEL at Barrow and commercial shipbuilder Kvaerner Govan to build HMS Ocean in the 1990s, and more recently with the Aircraft Carrier Alliance to build the Queen Elizabeth Class, but it has never been fully exploited.”

Scottish independence

Paul warned that Scottish independence could severely impact the shipbuilding industry, as a separate Scottish navy would generate only a fraction of the demand provided by UK defence contracts, particularly the Type 26 and Type 31 frigate programmes, which have driven the recent modernisation of shipyards in Govan, Scotstoun, and Rosyth.

Without these large-scale defence projects, the shipyards would lack the critical mass needed to sustain production, forcing them to rely on commercial diversification—a transition that Sweeney argues would be challenging without proper government support.

“As much as it is now a distant prospect, when I worked at BAE Systems during the 2014 referendum, we had a live contingency plan to eventually move operations to the sites at Barrow and Portsmouth in the event independence were to happen, after the Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier programme wound down. The simple fact is that the recent modernisation of the shipyards at Govan, Scotstoun and Rosyth has been stimulated by the demand signal created by the Type 26 and Type 31 frigate programmes for the UK Royal Navy. A separate Scottish navy would have a small fraction of that demand signal, which in isolation would be an insufficient critical mass to sustain production without commercial diversification.

To test this hypothetical scenario further, you only have to look at the debacle with the MV Glen Sannox and MV Glen Rosa at Ferguson Marine, which originated in the Scottish Government’s deal with Jim McColl’s Clyde Blowers Capital to rescue the shipyard from administration in August 2014, a month before the independence referendum.

That ferry programme has become a case study in how not to manage a commercial shipbuilding project, and despite operating the second largest public sector fleet after the Royal Navy, with 36 vessels, most of the new Caledonian MacBrayne fleet is now being built by Cemre Shipyard in Turkey due to the scandalous failure of the Scottish Government to make the most of that opportunity of reviving Ferguson Marine a decade ago to transform the shipyard into a competitive ‘ferry factory’ by leveraging the procurement of the CalMac fleet effectively.

So whilst those recent CalMac ferry orders flow overseas, it is only subcontract work from BAE Systems for the Type 26 programme that is keeping the Scottish Government-owned Ferguson Marine going at present, with its future hinging on winning CalMac’s Small Vessel Replacement Programme later this year. I have offered plenty of constructive ideas to the Scottish Government about how to improve our public procurement and using the state investment bank to provide ship finance products so as to support the development of commercial shipbuilding in Scotland like competitor nations do, but so far my suggestions have been ignored by Scottish Ministers.”

The Importance of Long-Term Planning

Sweeney repeatedly returned to the theme of long-term planning, arguing that the shipbuilding industry cannot thrive without a stable and predictable pipeline of work. He highlighted the risks of short-termism in government policy, particularly regarding Treasury constraints on multi-year capital financing:

“The Treasury’s accountancy-driven focus on yearly cost control militates against long-term economic value creation. This undermines the performance of major industrial programmes in naval shipbuilding, where stability and forward planning are essential to maintaining production efficiency.”

He also underscored the potential cost savings of a stable demand signal:

“When production is consistent, we see learning curves that significantly reduce costs over time. Longer UK production runs, like the Type 45 and Type 26 programmes, allow for efficiencies that are impossible in stop-start scenarios. If the UK were to consolidate its frigate and destroyer requirement into one integrated and virtually permanent production programme, like the Americans have done with the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, in almost constant production across four variants since the late 1980s, Britain’s shipbuilding enterprise would realise immense improvements in productivity and value for defence.”

A Vision for Collaboration and Integration

Sweeney’s proposed vision for the future involves a fully integrated, national shipbuilding champion—akin to Airbus or Boeing in their respective industries. Such an enterprise, he argued, would be better equipped to handle both defence and commercial shipbuilding demands:

“If we want to compete internationally, we need a national enterprise that operates as a single industrial champion. The idea of competing between British shipyards is nonsense. Real efficiency comes from understanding this is a national endeavour.”

This unified model would also facilitate the development of complementary commercial shipbuilding opportunities, ensuring that Scotland remains competitive in global markets.

Modernising Infrastructure for Future Demands

Sweeney highlighted the importance of modernising shipyard infrastructure to meet the demands of future shipbuilding projects. While praising recent investments on the Clyde and at Rosyth, he noted that further improvements could enhance productivity:

“If we could build a ‘Kompakt-Werft’ style shipyard like Meyer Werft in Germany and create a larger-scale indoor ship assembly facility for large commercial and naval vessel construction, at a site like Inchgreen where you already have the largest mainland dry dock in Britain to build over, that would be gamechanger for the industry in Scotland.”

He added that legacy infrastructure constraints remain a challenge, particularly at older sites like Govan:

“The shipyard at Govan was the world’s first integrated shipbuilding and marine engine works, so it is constrained by the legacy of 160-odd years of constant production. It’s not how you would design a shipyard today if you were starting with a greenfield site. While the processes have certainly improved considerably and will be further enhanced with the completion of the new Ship Assembly Hall on top of the filled in fitting-out basin in a few weeks, further improvements could still be made to optimise production.”

A Personal Connection to Shipbuilding

Reflecting on his upbringing, Sweeney shared his personal connection to the industry:

“I was brought up in the shadow of the stop-start, feast-and-famine cycles of shipbuilding production in the 1990s when my dad was made redundant from Yarrows. Growing up with the industry instilled a great sense of pride in building these great ships in Glasgow, but it was tempered with a sense of unease about its future. The spectre of decline was never far away.”

This early exposure to the challenges of the industry has fuelled his commitment to advocating for its growth:

“I’ve always had a real conviction that more should be done to build industries that we’re very proud of in Glasgow. An island nation like ours should unashamedly develop this specialism.”

The Way Forward

Sweeney concluded with a vision for the future of Scotland’s shipbuilding industry, calling for ambition, collaboration, and strategic investment:

“We’re an island. It’s remarkable that we don’t have a dedicated investment fund for the development of our shipbuilding and maritime industries. Our governments are way too risk averse when it comes to state aid. Take the Spanish Tax Lease system for example, which is applied to finance agreements for the purchase of ships, making it possible for shipping companies to purchase ships built by Spanish shipyards at a 20% to 30% discount. We need to get our act together, understand what competitor nations are achieving, and have the gumption to compete and win again.”

His message is clear: with the right policies, funding, and collaborative strategies, Scotland’s shipbuilding industry can not only thrive but lead on the global stage once again.

Great article and a sound plan, however meanwhile the government pushes back 2.5 per cent on defence and dithers over new ship orders

I’m not sure the ‘natural monopoly’ plan of reviving BSL is in any way sound.

The fact that BAE got their best pencil sharpener out when Babcock came along signals that in itself.

The main thing is to keep the orders rolling through at a fast step commercial pace optimised to keep build costs down and get best value. That actually means a larger fleet of combatants is needed – well it is we all know that! If you think that BAE wanted to build T26 faster for commercial reasons that is a bit of a hint.

I agree, aircraft carrier alliance model single source supplier was always a disaster if the companies are private for profit enterprises.

Unfortunately the orders are not going to keep rolling, there are foreseeable gaps in all the current shipyards

Yep. We effectively has a single ship builder BAe and they showed no appetite to invest, wanted government funds to build a factory and produced some tge most overpriced OPVs ever made.

It’s proven time time again competition drives better prices high quality and RnD in new processes.

What’s needed is enough orders and yards to be completing for commercial orders rather than relying on the government.

BAE will never build a commercial vessel, because they arent commercial, if they or Babcock had to operate as a commercial shipbuilder they’d be closed within 12 months. When did they last build a ship that was on time and on budget, without the MoD/Govt rescue hand outs. T31 have already done that and the first boat isn’t even in the water yet!

the dithering is in the canteens in the yards, serving idle workers in the third tea break of the morning

Sorry but this guy is going in to bat for Scotland not the UK

C olin Brooks

You mean like how Andy Burnham goes into bat for Manchester of Sadiq Khan for London.

The guys an MSP, batting for Scotland is his job.

Sorry but this guy is going in to bat for Scotland not the UK

Colin Brooks

I stopped reading at MSP. Fed up with the so and so’s.

When the government gives a tax rebate of up to 40% for TV and Movie productions in the UK it’s hard to argue shipping should not get the same, I dare say if they made ships in north of London it would. We are happy to cut Disney a cheque each year for several billion for the sludge they apparently make in the UK. It would be far more productive to put this into ships like the Spanish.

these film types always bring in their own staff and equipment so the only economic boost is the butty van but then fat Sid only takes cash.

Is the Norwegen selection this year?

Norwegian

Not sure when the final selection is, but France (FDI), Germany (F126), UK (T26) and the US (Constellation) have been down selected to the final stages of the selection process. The is a good article on Naval Technology and from what they state the T26 is in a good position, but might require flexibility on behalf of the RN given the Norwegian requirement for early delivery one of the RN’s ships currently under construction might need a name change in Norwegian…

The the hassles the USN is having with the Constellation Class I would think that is an outsider, although who can tell what kind of political pressure might be applied. The French FDI is a light multi-purpose frigate at 4,500 tons, not a specialist ASW platform. The German F126 is big at 10,500tons and is also supposedly a multi-purpose ship. Too big perhaps..?

Cheers CR

FDI is probably the cheapest though and has much better AAW

Yeah, I am aware of the competitors. I was just wondering when the selection going to be made roughly. Thanks.

Australia has already reduced their order of Type 26s, due to it not satisfying requirements, there is no margin left as the design is too heavy to enable them to change the design for what mods they had intended, and Aus are now in the market for a replacement. It’s not the best platform by far.

For ASW it’s the best Platform, Aistrlia picked the wrong vessel if they wanted a universal role ship.

Don’t disagree with much of what he says, but it comes down to how are we going to pay for it? If his party didn’t give out bumper pay days to his Union friends, maybe we would have a chance.

Unfortunately a lot of the issue is not just treasury annual accounting, although that is a massive issue it’s from the actions of the MOD and RN in the 1990s and 2020s. Simply put:

1) The RN blew a lot of money to gain marginal capability increases on the T45 over the horizon program..linked in with basically throwing a hissy fit at the French and Italians and walking away cost a fortune..it’s very likely that if the RN and MOD had stuck with horizon they would have had 8 even 9 or 10 destroyers….they pissed the cash away.

2) frigates..the RN and MOD basically lost their collective box on what a frigate was and what it was for..basically pissed around for 20 years and blew billions.. even after moving from horizon to T45 there was a good plan on the table to keep escort numbers up and that was to build the hell out of the T45 hull..essentially creating 10 AAW, 10 GP versions and 10 ASW versions with a quilted hull…this was considered the most conservative and likely to succeed programme..but the RN essentially lost its rocker and spent time and money trying to decided what a frigate was…in the end it ran out of time and got Cameron…and a navy of 30 was cut and cut and delayed and delayed..if the RN at the very beginning had just gone OK 45s we will build 30 in three versons where do we sign…we could have had a different navy.

Don’t see how we’d be in a good position with 30 barges with bad engines, and terrible ASW

Well the plan was to make 10 of them silenced hull with tails.

I’m not aware of any serious proposal to build out T45 into a run of 30 of various types.

Early on there was a vague idea of that.

As far as I’m aware they never crystallised into design work never mind contract proposals.

Work on the GCS and its progenitor was going in long before Horizon was ever an idea.

Simply put if RN had acceded to French demands the radar system that it had spent £100ms on since 1986(ish) – yes that long ago – would never have seen the light of day.

At the time I was on the fence about in or out of Horizon but I do believe, with the benefit of 20-20 hindsight, that the right decision had been made.

We all get very hung up on the WR21 issue but apart from that T45 is a really good AAW platform that us way better than Horizon in a lot of key respects.

Interestingly if you go back and review all the old papers on the various iterations and studies from the 2000s the idea of 20 frigate versions of the T45 was up there as the lowest risk concept to take forward.

UK could have made an Horizon replica with its own radar.

Engine issues aside T45 is a good design, and like any complex vessel you need to amortise the R&D costs across multiple examples to lower the price-tag. I believe BAE were offering T45 7&8 for £750 million a piece before the class was curtailed at 6.

We also spent all that money on them and then saved peripheral amounts by not fitting things like Harpoon and 12 extra VLS, which we are finally starting to rectify with NSM and Sea Ceptor.

There is a reason why ship building for the navy has been stop start, the defence budget hasn’t been big enough to sustain requirements, why only 6 destroyers, MOD couldn’t afford more.

The only way to improve matters is for the government to have a plan and STICK to it. The ship building industry can’t even trust that building the first type 26, all 8 will get built (designed for 13 to be built remember,) how can anyone plan against that backdrop.

It would have been 13 if the prices had been more sensible.

Essentially BAE were an inefficient monopoly supplier and named a price that suited them.

OK they know MoD can be a nightmare customer but in the absence of competition…..

The idea of an effectively continuous building programme makes sense. With a fleet of between 19 and 25 surface escorts, turning out one per year ought to be straightforward to organize. Keeping to a basic proven design as the US has done with the ABs should help sustain existing supply chains, helping to keep costs down. Small numbers( 6+8+5)of completely different designs cannot be efficient. A core design, flexible enough to allow easy upgrades of sensors and weapons, should deliver cost savings and maybe extra numbers.

Except we still haven’t found a universal design that meets all our standards in ASW and AAW and doubt we will as those standards are high and so are costs for each specialist class

Building one design for 30 or 40 years comes at a price as the USN has discovered. You find you end up with no designers and have to buy an Italian design that has to be enlarged for Pacific ranges and USN weaponry and systems etc.

The US decided its new frigate had to be an in service design to reduce the risks of a completely new platform. I guess this was partly determined by the experience with the LCS, two brand designs that suffered large delays and cost overruns and proved to be of very limited use. But then the USN demanded major changes to the original design which have already caused delays and cost increases.

A single base platform may be sub optimal, but with the size of the current generation of escorts so much larger than their predecessors, they are inherently more flexible. If we continue down the route of optimal specialised designs, the high costs will mean numbers will be constrained.

It is is the same with T26 for Australia and Canada. Changes imply time and $$$ is needed to fix new problems and add new capabilities.

No union has had a payrise from any government only workers get payrises. The unions are payed by their members.

Maybe look at re-jigging to camper’s and motorhomes, as the SNP and its corrupt head sheds like to own one each!

One off the areas for concern, and a precursor to late deliveries,cost over runs,is the design side. Due to as the report mentions a huge gap in apprentices, which included the design office side there is now a masssive gap in experience, expertise due to the grey beards retiring or dying, and there being nobody, or at least nowhere near enough people, to pass on their knowledge too. The yards are now full of draughtsmen and engineers who have been dragged in from secotrs such as aerospace, automotive, civil, etc (at all levels, from draughy to directors) who haven’t got the first clue about shipdesign, nor shipbuilding. There lies a huge issue, that impacts far more than people seem to realise.

Shipbuilding needs experience of people who have designed and built ships, not planes, cars, or nuclear concrete bunkers.

Do you think the Fincantieri or Navantia or Cenre or Damens of this world are using people from aerospace/automotive in their businesses, damn right their not. Horses for courses.

I was drunk over the weekend. I imagined that EU + UK broke up with Nato and formed a new Euro Security alliance. The stupiditus was Russia and Ukraine was brought into the new family. It was old Donnie’s tariffs that caused the kerfuffle and threats over Greenland. And Europe finally got upset at ridiculous high energy prices when Russia sells at discounted prices. Scotland would then build warships at a reasonable pace. UK, Germany could develop Ukraine instead of American giant corporations. I got to drink less.

Hi George, I was one of the industrial engineering team based at Govan Shipbuilders in the late 70’s when we were building the data base for the whole of British Shipbuilding, almost all of us taken from the shop floor and trained in industrial engineering. All trades were represented so we knew most of the dodges,shall we say. Most of the team were enthusiastic and brought with them fresh ideas gleaned from working on the shop floor but there was no appreciation of their efforts shown by management and if this was indicative of the industry, it is no wonder it sank (excuse the pun). I know it may sound like sour grapes but let me relate an example. The yard was trying to reduce the time taken to build a hatch coming from ten to seven days. I designed a jig that reduced it to four days which I duly submitted and heard no more about it until I came across it while doing an activity sample. When I asked my manager why I had received no feedback he replied, “what do you want, a chocolate watch”. How to kill initiative in one easy lesson. Regards, John.