Britain’s forgotten prison island: remembering the thousands of convicts who died working in Bermuda’s dockyards

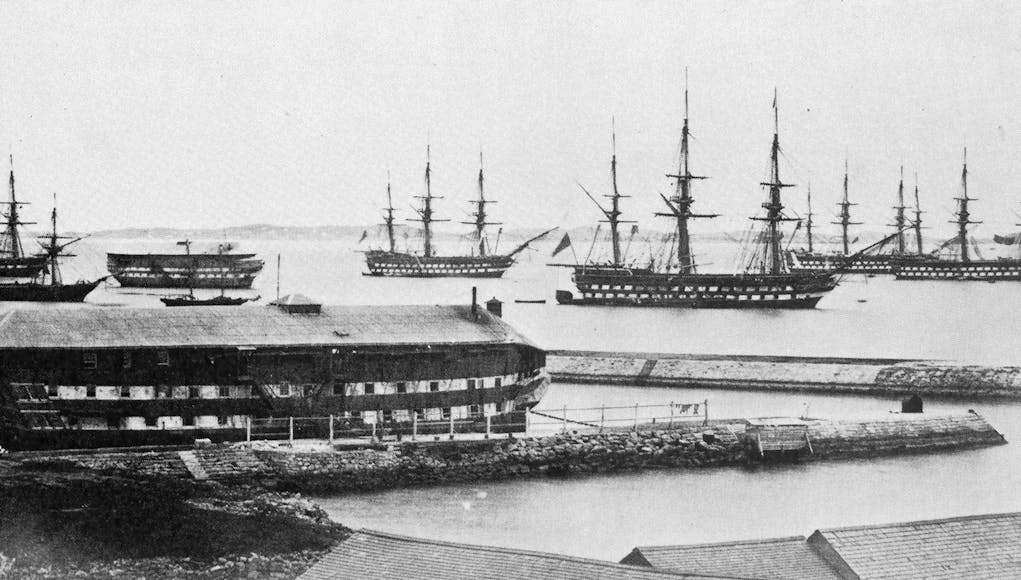

We think of Bermuda as a tiny paradise in the North Atlantic. But long before cruise ships moored up, prison ships carried hundreds of convicts to the island, first docking in 1824 and remaining there for decades.

Islands have long been places to deport, exile and banish criminals. Think of Alcatraz, the infamous penitentiary in San Francisco, or Robben Island in South Africa, which held Nelson Mandela.

The French penal colony Devil’s Island was immortalised in the Steve McQueen film Papillon, while Saint Helena in the Atlantic is still remembered for Napoleon’s exile.

This article is the opinion of the author Anna McKay, Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellow in History, University of Liverpool and not necessarily that of the UK Defence Journal. If you would like to submit your own article on this topic or any other, please see our submission guidelines.

You may be familiar with the story of British convict transportation to Australia between 1788 and 1868, but the use of Bermuda as a prison destination is less well known. For 40 years, British prisoners worked backbreaking days labouring in Bermuda’s dockyards and died in their thousands.

I research the lives of prisoners across the British Empire, and have a particular interest in notorious floating prisons known as hulks. I was surprised to discover that in addition to locations across the Thames Estuary, Portsmouth and Plymouth, the British government used these ships as emergency detention centres in colonial outposts across the 19th century, detaining convicts in Bermuda between 1824 and 1863 and Gibraltar between 1842 and 1875.

England has a long history of banishing its criminal population. In the 18th century, criminals were typically sentenced to seven years overseas in America. Many worked as plantation labourers in Maryland and Virginia, but the start of the American Revolution brought this practice to a halt.

Britain believed that the war with America would end quickly and in its favour, but as the war continued, prisons filled with people who had nowhere to go. There was no emphasis on reforming prisoners and releasing them back into society.

Britain found itself with a prison housing crisis, and turned to hulks to cope with rising numbers. Each could hold between 300 and 500 men, and they were nicknamed “floating hells” for their unsanitary and dangerous conditions.

Officials proposed several locations to send convicts, and ultimately settled on Australia. But the government felt that convict labour could be put to use in other colonies, and so began an experiment in 1824 to send men to Bermuda.

Convict workers

Bermuda had been colonised by British settlers since the 17th century, and was governed by various trading companies until 1684 when the Crown took over. Though only 20 miles long, the island was already extremely important to naval strategy. It was used as a refuelling station for British ships travelling to colonial outposts such as Halifax, Nova Scotia and the Caribbean.

But the naval dockyard needed modernisation, and rather than employ local workers, convicts – a cheap and easily mobilised workforce – filled the labour gap.

Bermuda didn’t have a large prison, so men lived on board the ships they had sailed on (seven in total). Local traders, shipbuilders and whalers objected, complaining in newspapers that the government was sending a “swarm of felons” to the island. The government offered a compromise: no convicts would remain on the island at the end of their sentences. Instead, they had to return home, or travel on to Australia.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Work on the island wasn’t without risk. Many were injured in the dockyards, others went blind from the reflected glare of the sun as they quarried white limestone.

Convicts were at the mercy of hurricanes which battered the ships and caused injuries. They were burnt by scorching temperatures and suffered sunstroke, and the island’s humidity caused respiratory problems and spread deadly fevers on board.

Rising tensions over work, religion and alcohol consumption led to fights between prisoners, their overseers and the militias that guarded them. Some attempted escapes by stealing boats and trying to board ships bound for America.

Bermuda also received people convicted in other British colonies, including Canada and the Caribbean. During the years of the great famine in Ireland (1845 to 1852), thousands of Irish convicts arrived on the island, many suffering from malnourishment. This diversity was striking when compared to prisons in England.

The experiment ended after 40 years, in 1863, when dockyard repairs were completed. The remaining hulks were scuttled or broken up for scrap, and convicts were transported to Australia and Tasmania, or home to England with their meagre pay in their pockets.

Prison islands today

Prison islands are naturally isolated and cut off from land – escape is virtually impossible. Then and now, they enable states to lay claim to land, facilitate trade and secure commercial ambitions. Islands have many strategic advantages and are frequently used as military bases. Now, many former prison islands are Unesco world heritage sites, and tourist destinations.

Bermuda’s history as a prison island has been largely forgotten, but this story shares parallels with today. Prisons are suffering from overcrowding, and governments still detain prisoners and others on islands and modified ships.

In Dorset, the Bibby Stockholm ship is housing asylum seekers, while the island of Diego Garcia, used as a UK-US military base is detaining Tamil refugees in the Indian Ocean.

The convicts who lived, worked and died in Bermuda are part of a larger global story of coercion and empire. The product of their labour was imperial strength, but for those sent thousands of miles from home and buried in unmarked graves, the brutalities of their experience should also be remembered.![]()

Anna McKay, Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellow in History, University of Liverpool. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shock, horror hold the front page, “The British Empire” kept prisoners in horrible conditions inside prisons (Albeit here on ships). It was a different age not just for the Uk, but for the entire human race, for example the UK kept them in prisons, in contrast east of (and including) the Ottoman Empire (The Ottomans didn’t officially (Cough, cough) ban slavery until 1890 with the signing of the Brussels Conference Act ) .more than likely you would have been turned into chattel until the day you died if banged up. In contrast those (other than those who died) convicts kept on British floating prisons were released (more on that later)

I feel the author could have explained a little more on why the use of prison hulks came about. The national archives has a most comprehensive, well researched speech given by historian Jeff James the director of operations and services at The National Archives in 2012.(its also a pod cast)

Can be found by searching on for the National archives

Prison hulks Friday 24 February 2012 | Jeff James

And I quote:

So in a nutshell it was about a glut of prisoners again I quote from the above article:

I have no issues with people knocking out historical articles , but they have to be actuate, factual and without any form of bias. The article I highlight above by does just that (well it is a national archive one) but the above one doesn’t which is why the only link it posts is regards the naval version of Burke and Hare which is used as a sledgehammer to condemn the entire act. And by slipping in this:

I’m sorry, but the Bibby Stockholm is a open accommodation barge, the people held on there are free to come and go as they wish, there is a free bus service from the barge to Weymouth I quote from the Dorset echo dated 24/02/24:

Nobody complained when Germany and Holland used the Bibby Stockton to house asylum seekers, nor when it was used as accommodation for workers in Scotland and Sweden, but when the Uk Gov uses it , why it’s a human rights crime, the same with Diego Garcia where the so called inmates demand to be relocated to the Uk, which is why they took the UK to court stopping them from been returned home.

As I mentioned above, I have no problem with factual free from bias historical articles all I see above is an article which uses the morals of today in which to judge the actions of yesteryear. I really do recommend the national archive article.

Oh regards my more later bit in brackets, the article I mentioned lists a large of prisoners who were arrested, charged , jailed and released.

I have to laugh at this comment:

Why ? because the author links in to a Guardian article from a fortnight ago which states the following:

Prisoners could be let out 60 days early to relieve crowded jails in England and Wales

Last week saw a vicious nasty knife attack on a train in London (caught on film) the attacker 19 year old Rakeem Thomas has been arrested and charged after he became famous on social media. Well guess what, it transpires he was jailed in late Dec for 6 months for getting caught carrying a huge knife. Just think if he hadn’t been released at least 3 months early that poor man who is currently in intensive care would be enjoying Easter Sunday with friends and family.

Farouk, like you, I was reading the article with a bit of interest, knowing some but not a lot about the use of Naval hulks as prison ships. Didn’t we house loads of French sailors in them at one time.

Like you, I found it reasonably interesting until the “shock – horror” piece about Weymouth. Sadly at that point the “guest contributor” lost all credibility with me.

George, please don’t invite her back.

I second that.

Mark,

A little digging on her name reveals that the conversation article it was first posted on, is actually a heavily edited iteration of the original paper she wrote on the subject (as gleaned from her twitter site)

Asylum Barges in historical context: Britain’s prison hulks expose fault lines in today’s policy

Executive Summary

As i mentioned, I have no issues with historical articles that are factual and without revisionist bias . But I am getting sick to the back teeth with how history is been tainted in which to promote a PC version for those with an axe to grind. The Guardian knocked out something similar this week about graves of slaves found on St Helena when they were building the airport. The person writing the article is surreptitiously allowed to claim that the graves was due to the British slave trade (changed to admit in the following articles that the people on ST were actually freed slaves whom the RN East Africa squadron had intercepted, then they go on about how they are taking the Uk to court regards having the remains (now reburied at St Michaels church on the Island) with demands to repatriate the bodies to Africa. But the interesting thing in the last article is how people in the Uk are pushing for the recognition of how Great Britain went out of its way (on its own at that) to end the Atlantic slave trade. I quote:

It’s not unpatriotic to tell the whole truth about Britain and the end of slavery

The thing is Denmark wasn’t the first to end the slave trade, it ended its participation in the Atlantic slave trade in 1792, it didn’t end slavery until 1847 and that was helped with a deal that Great Britian signed with Denmark in 1835 (like it did with many other countries, usually by paying them to do so) How can I substantiate this because it the Nation Museum of Denmark has an entire webpage on the subject in English:

Danish Colonies / The Danish West Indies / The Abolition of Slavery

The Abolition of Slavery in 1848

Then the article berates Great Britain for only rescuing 150k poor souls between 1808–1867 (59 years) which is a drop in the ocean over the total figure (Between 1526 to 1867) of 3 million people . Gee the thanks you get for being the first nation to use its wealth, Navy and the lives of 1500 sailors between 1830 to 1865) to do the right thing. This the article further ridicules by stating:

Sick to death with this constant downplaying of the good the UK did and now they are trying to erase that by the use of misinformation by omission.

England has a good claim to be amongst the earliest, though not the first, as slavery was originally banned at the the Synod of London in 1120 (the Normans had banned slavery in Normandy before 1066).

As a religious edict, it had no legal force, but the Church backed it with the threat of excommunication. Slavery had vanished from England by 1180, replaced by serfdom, until that fell apart following the Black Death.

Research this. The whole thing has a “Guardian” feel about it. You will feel guilty about history. That thing that was made by dead people. Very biased and very left wing.

Oh the Guardian. An institution that was funded by slaver money. But because they’ve admitted it they think its all ok. And slag off everyone else instead….

I was thinking Australia to be fair.

I look forward to your next in depth article on how the nasty British Empire was among the first to abolish slavery and the Royal Navy’s role in intercepting foreign shipping transporting slaves and carrying them to freedom – Freetown in Sierra Leone or service in the RN among the options offered to the recently incarcerated.

Also look forward to your follow up piece on the plight of young single men choosing to relocate to racist far right Tory England fleeing the living hell that is war ravaged France – you know, that place where wealthy middle class socialists often choose to buy a second home.

Ironically, the old Casemates Barracks in Dockyard, built by those convicts and where the gaolers probably lived, became Bermuda’s prison.

Locally referred to as the Casemates Hotel, or sometimes as Casa Maté

Edited – it was the prison until 1995

g.ms Marabar

as the harbour came to be known was and still could be a perfect location to base a counter drug/snuggling ship the old bas on Ireland island is now a popular destination for tourists worth a Google

i use ancestry to trace my ancestor, I found that one of my great grand uncles had been transported for stealing a sack of coal and a pair of boots from a shop in Stafford the records show the hulk used was the destiny which arrived in botany bay two months after leaving Portsmouth